|

Welcome to

the Hay Historical Society web-site newsletter

No. 7. Included in the newsletter

is:

- Information (and a link) to a

recently-added web-page of biographical

details of Wesleyan / Methodist ministers

at Hay until 1901.

-

- A feature article called Hay

during World War I: Rev. B. Linden Webb

and the Hay Methodist

Congregation. It is the story

of the Methodist minister Rev. Webb who

served at Hay for two-and-a-half years

during World War I, during which he

expressed his moral opposition to the war

from the Hay church pulpit. The

article traces his story, including the

ensuing interactions between Rev.

Webb and members of his

congregation.

This newsletter is best viewed full-screen due

to the incorporation of graphics.

WEB-SITE SEARCH FACILITY. –

With the steadily-growing size of the Hay

Historical Society web-site a facility has

been added to allow searches to be carried

out of all pages within the

web-site. The search-engine –

called Pico Search – can be found on

the title page

WESLEYAN / METHODIST MINISTERS AT HAY (TO

1901). – A web-page has been recently

added with information about the Wesleyan /

Methodist ministers at Hay from 1871 (when Hay

was regularly visited by Rev. Charles Jones

from Deniliquin) until 1901. Twelve

ministers are featured, most of whom were

appointed to the Hay circuit (the first being

Rev. William Weston in 1872). The

policy of the

Methodist

Church was to appoint ministers to circuits for

short periods; initial appointments in New

South Wales were for one year, with each

successive year renewable to a maximum of three

years. The constant turn-over of

ministers between circuits enabled centralised

and disciplinary control over the ministry and

is considered a factor in the steady growth of

Methodism during the nineteenth century.

Biographical details, lists of ministerial

appointments and (in most cases) photographs of

the ministers are included on the

web-page. [see: link]

Hay during World

War I:

Rev. B.

Linden Webb and the Hay Methodist

Congregation

A cherished and defining historical motif of

the Hay community is the large number of

military volunteers from the township and

surrounding district that served during World

War I. The honour board at the Hay War

Memorial High School lists a total of 642 men

and women who enlisted for service during the

1914-18 war, one of the highest per

capita enlistment rates in

Australia. Of this number fifteen

volunteers were from the small Methodist

congregation at Hay. In the early months

of the conflict the local recruiting sergeant

requested assistance from the clergymen of Hay

to encourage and appeal to the young men of

their congregations to enlist. The

recruiter received support from each of the

local clergy, with a single exception.

The young Methodist minister, Rev. B. Linden

Webb, rejected the request and refused to be an

agent of recruitment to the Australian armed

forces. Furthermore, in the early months

of 1915, Rev. Webb preached a series of sermons

in the Hay Methodist church presenting a moral

case against the war. Later that year he

published his pacifist sermons in a pamphlet

called The Religious Significance of the

War, which caused a degree of agitation

within the broader Methodist Church. Webb

remained at Hay until October 1917 when he

resigned due to irreconcilable differences with

the leadership of the Methodist Church,

particularly in regard to the Church's official

stance on conscription. Against the

background of a virulent and divisive national

conscription debate the story of Rev. Webb's

two-and-a-half years at Hay involves a dynamic

interplay between the minister and his

parishioners which, considering the underlying

emotive issues, was characterised by a

remarkable degree of tolerance and restraint.

Bernard Linden Webb was born at Bathurst on 25

November 1884, the fourth of six children of

Edmund and Fanny Webb. The Webbs were

"one of the most numerous and devout Methodist

families of the region". Linden Webb had

planned to become a lawyer, but during his

second year at Sydney University "he felt the

call to preach"

[Linder]. Webb completed a

Bachelor of Arts in 1906, after which he

attended the Methodist theological training

school, Newington College.

During 1908

Webb served as a probationer

in the North

Sydney circuit. From early 1909 to

early 1911 he served at Moss Vale,

NSW. In 1911 Bernard Linden Webb and

Eleanor Dunbar were married (registered at

St. Leonards); the couple had met during

Webb's probationary period at North

Sydney. Linden Webb took leave of

absence in 1911 to travel to

England. In 1912 Rev. Webb served at

Tighe's Hill in the

Hamilton-Wickham circuit (Newcastle region). A

bout of ill-health required him to rest

from active ministry for part of 1913;

during that period Rev. Webb was based at

the Central Methodist Mission at 139

Castlereagh Street in Sydney.

Rev. Webb at

Hay

In March 1914 the New South Wales Methodist

Conference assigned Rev. B. Linden Webb to the

Hay circuit to replace Rev. Charles Thomson

Lusby (who had been appointed to Albury).

Webb arrived with his family at Hay on

Thursday, 16 April 1914, and on the following

Sunday he preached his first sermons in the

township as part of the Methodist Church

anniversary celebrations.

[Riverine Grazier, 10 March 1914, p.

2; 21 April 1914, p. 2]

The Hay

church embraced its new young minister, his

charming wife and two-year-old son with

considerable enthusiasm. The early months

were filled with activity: preparing and

preaching sermons, pastoral and hospital

visitation, travelling to various preaching

stations in the Riverina, marriages and

funerals, providing leadership for the local

Band of Hope temperance group, and attending

and encouraging the Methodist Literary and

Debating Society.

[Linder]

Linden Webb arrived at Hay four months prior to

the outbreak of the First World War.

Tensions between European nations escalated

into full-scale war in August 1914. The

initial response in Australia to the outbreak

of hostilities was a surge of patriotic support

for Britain. The degree of Australia's

emotional ties to 'the mother country' was

manifested in the large number of volunteers

for military service and supportive rhetoric

from many of the nation's political and social

leaders. Most of the Protestant

churches in Australia, including the

Methodists, expressed support for

Britain. The Methodist leadership

considered the British cause as righteous, a

view perhaps exemplified by the words of Rev.

Dr. W. H. Fitchett in the wake of the Gallipoli

landings: "It is God's cause, and not –

in any selfish sense – ours, for which we

fight; and we may humbly dare to believe that

God is with us"

[The Methodist, 19 June 1915, p.

1]. Methodist Church historians

Don Wright and Eric Clancy contend that the New

South Wales Methodist Church was by that stage

incapable of a mature response to the

challenges of the Great War and the social and

political upheavals of the times.

It had no

theology of war and peace and, for the most

part, neither clergy nor people had thought

deeply about the relation of the Gospel to

international affairs. Nor was a church

which was only slowly emerging from the

intensely individualistic religion of an

earlier day well-placed to take so large an

intellectual step. All it had was a

resolution passed at the 1914 Conference, which

committed Methodism both to defend the Empire

and to pray that the time would come speedily

when 'nations shall learn war no more'.

In any case, New South Wales Methodists, like

their fellow citizens of all faiths, were

imperialists to the core and unlikely to do

other than support Britain in its hour of

need. [Wright

& Clancy p. 130]

There is, nonetheless, some evidence of a more

ambivalent attitude held by some members of the

Methodist community to Australia's

participation in the war. Furthermore the

actions of Rev. Webb were soon to provide a

catalyst for the expression of oppositional

perspectives from within the Methodist clergy

and laity. The historian Robert D. Linder

considers this mixture of responses as

indicative of the nature of Methodism:

The roots

of this paradox lies in the historic dynamics

of Methodism itself: fervently evangelical in

theology, fervently evangelistic in

orientation, and fervently committed to

self-improvement and moral attainment in

ethics. Their evangelical theology

assured that some Methodists would take a close

look at the war through the lens of

Scripture. Their evangelistic orientation

meant that most Methodists would see

opportunities for winning souls to Christ, even

in the midst of war. The commitment to

self-improvement and a high moral standard

meant that many Methodists would be less

concerned lest military life ruin or damage

their young men's spiritual well-being.

Moreover, Australian Methodists before the war

had close ties with their German counterparts,

which may have led some to pause before

launching into rhetorical tirades against the

enemy. A combination of these factors

helps explain the seeming ambivalence of many

Methodists concerning the war.

[Linder]

Australians had very little direct experience

of combat in the initial phase of the war

during the remaining months of 1914.

Federal elections were held in September in

Australia, with the new Labor Prime Minister,

Andrew Fisher, taking office. On 1

November 1914 the first contingent of 30,000

Australians and New Zealanders departed from

Albany in Western Australia for further

training abroad. The Australian cruiser

HMAS Sydney, on escort duty

with the Anzac troops, engaged and succeeded in

sinking the German cruiser SMS

Emden near the Cocas (Keeling)

Islands. A second body

of troops sailed in December. By then

over 52,000 men had enlisted in the Australian

Imperial Force (AIF), with the rush of

recruits continuing unabated. These

events contributed to an early sense of

optimism and enthusiasm in Australia and there

was a widespread belief that the war would soon

be over. By year's end, however, reports

from Europe had dispelled this expectation and

it had become apparent that Australian soldiers

would be participating in the

fighting.

By the time of Rev. Linden Webb's arrival at

Hay there is little doubt that he already had

firm views about war and strongly believed that

State-sponsored violence was contrary to

Christian teachings.

Reports

of the Boer War (1899-1902) had caused a young

Linden Webb to question the use of violence to

settle international disputes. By the

time he arrived in Hay in 1914, he already had

concluded that killing and violence in the name

of the state was contrary to the teachings of

Jesus Christ. [Linder]

The widespread Australian enthusiasm for the

war in the latter part of 1914 "deeply affected

the young Methodist clergyman and led him to

brood over the situation in Hay".

[Rev.

Webb] had rejected the entreaties of the

local recruiting sergeant to urge enlistment in

the ranks of the AIF. He now asked

himself if he could and should do more?

[Linder]

In the end Rev. Webb resolved to take a public

stand and deliver a series of sermons against

war from the pulpit of Hay Methodist

church.

The first Sunday of the year 1915 (3 January)

was designated by the major Australian church

groups as a national day of prayer and

intercession in connection with the war.

Ministers were encouraged to preach about the

war on that day, with the tacit expectation

that they would assert the righteousness of the

cause and perhaps provide an explication of the

role of conflict in the promotion of spiritual

regeneration. However, Linden Webb used

this opportunity to preach the first of his

pacifist sermons, entitled "The War and

Christian Ideals". He based his sermon on

the Biblical text, John 18:36: "Jesus answered:

My kingdom is not of this world, if my kingdom

were of this world then would my servants

fight, that I should not be delivered to the

Jews; but now is my Kingdom not from hence".

In this

initial sermon... the true church, he argued,

was composed of true Christians who truly

followed the true teachings of Jesus... Webb

sharply differentiated between those who truly

embraced Christ and lived according to his

teachings and those who professed Christian

faith but lived according to the materialistic

standards of the world.

[Linder]

Webb declared: "Not the soldier, but the

missionary, is the agent by whom Christ's

lordship is to be established". Later in

the sermon he stated that:

... the

sacrifice of men fighting for their country has

been compared to the sacrifice of Christ.

That is a terrible blasphemy!

[Webb, The Religious Significance of the

War, pp. 10; 15]

This sermon (as well as the two others in the

series) utilised the historical-grammatical

method of biblical hermeneutics (the theory and

methodology of interpretation of scriptural

text). It was a popular method amongst

evangelical preachers. The

historical-grammatical method is based on the

premise that a certain passage has only a

single meaning or sense.

A

fundamental principle in grammatico-historical

exposition is that the words and sentences can

have but one significance in one and the same

connection. The moment we neglect this

principle we drift out upon a sea of

uncertainty and conjecture.

[Terry, p.

205]

The aim of the historical-grammatical method is

to discover the original intended meaning of

the passage. The meaning is investigated

by utilising a multi-faceted approach,

examining grammatical and syntactical aspects,

the historical and sociological background, as

well as literary and theological

viewpoints. Furthermore, the

historical-grammatical method allows for the

investigation and interpretation of the

significance of the chosen text in order to

determine its application to present-day

circumstances.

On 21 February Rev. Webb presented his second

sermon at Hay, "The War as a Problem to Faith",

based on the Biblical passage: "And because

iniquity shall abound, the love of many shall

wax cold / But he that shall endure unto the

end, the same shall be saved" (Matthew

24:12-13). He concluded this sermon with

words reminiscent of Martin Luther: "We stand

with Christ though all the world be against us"

[Linder; Webb, The Religious Significance

of the War, p. 48].

A month later, on 21 March 1915, Webb delivered

the last of his trilogy of sermons, entitled

"The War and the Churches". This one was

based on 2 Corinthians 10:3-4: "For though we

walk in the flesh, we do not war after the

flesh: / (For the weapons of our warfare are

not carnal, but mighty through God to the

pulling down of strongholds;)". The

sermon began:

To put

the teaching in a general form we may say

first, that Christianity does not aim to assert

her authority over men by worldly methods, nor

does she depend on such methods to maintain her

cause; and, second, that Christianity has

weapons which are ultimately effective for

bringing all "to the obedience of

Christ". Surely, no one who has studied

this text in connection with the chapter in

which occurs can deny that those two

propositions are a faithful representation of

its meaning. A further deduction, which

we shall presently justify, is that the

Christian Church should restrict herself to the

use of her own weapons, which are not carnal,

but spiritual. [Webb, The Religious

Significance of the War, p.

24]

Towards the end of this sermon Rev. Webb said:

It would

be a very simple matter for me to stand up and

preach the righteousness of war, as so many

others are doing, but before God I

cannot. Nothing less than the ideal of

Christ will do! [Webb, ibid., p.

39]

He concluded the sermon with the question: "It

is of very little moment to the Churches if I

am wrong; but if I am right, what then?"

The general conclusion of Webb's trilogy of

sermons "was that war was immoral and based on

selfish materialism, not the Gospel of Jesus

Christ".

However,

for true believers, God had given a sufficient

revelation in Scripture and Jesus Christ, and

Christians must be absolutely faithful to the

teachings of Christ. In all three

sermons, Webb stressed "the moral damage of

war'', and emphasized the point that the

current conflict was a moral issue which

Christians could not ignore: "The war is not

keeping with our profession of Christianity; it

is the outcome of materialism worldliness,

godlessness".

[Linder]

|

| The

Bulletin (28 October 1915), cover drawing by

Norman Lindsay:

wartime propaganda incorporating

religious imagery. The text

reads: "THE NEW

CRUCIFIXION.

Jerusalem, Samaria and the Mount

of Olives have been turned into

Turkish drill areas under German

control; and at Golgotha (or

Calvary) rifle butts have been

erected, where the Turk may learn

to shoot the

Christian". |

By mid-year 1915 Rev. B. Linden Webb published

his sermons as a pamphlet entitled The

Religious Significance of the War.

The pamphlet was printed with the financial

assistance of William Cooper, a Quaker anti-war

activist, and the Sydney Society of Friends

[Linder], and was circulated by the

Methodist Book Depot. Webb's pamphlet

aroused unfavorable editorial comment in the

church newspaper, The Methodist.

The editor, Rev. Dr. J. E. Carruthers, had

previously described the conflict between

Britain and Germany as a "holy war", so his

negative response to Webb's views is not

surprising. The review of The

Religious Significance of the War in June

1915, almost certainly written by Carruthers,

severely criticized Webb's Christian pacifism

and concluded:

Theories

are easily propounded, but unfortunately we are

in the midst of great practical realities, and

the Empire would be in a sorry plight if it

were led by theorists who turn the blind eye to

the stern facts that must perforce be dealt

with.

[The Methodist, 26 June 1915]

Another review in the same issue, written by

'A.F.C.', stated that Webb's writings had an

"absence of clear logical perception and

reasoning [which] pervades the whole

dissertation and vitiates its

conclusions!".

Webb's pamphlet and the reviews of it in

The Methodist stimulated a large

amount of correspondence. The first

letter, published on 3 July, was censorious of

Webb's viewpoint and concluded with the

following remarks:

When the

Empire needs every ounce of strength to pull it

through, what are these men thinking of when

they air their theories to paralyse effort and

disparage practical patriotism?

['B.W.', The

Methodist, 3 July 1915, p.

6]

A response to the letter by 'B.W.' was

published on 17 July. The writer,

apparently a Methodist minister but signed with

the pseudonym 'Pax', reminded the journal's

readers that "there are those who regard the

appearance of Mr. Webb's pamphlet as timely in

seeking to recall the church to a sense of its

duty". The letter continued:

After the

war is over there will be a lot of clearing-up

work for the church to do, and the power of the

church then will depend to a very large extent

upon its attitude to the ideals of Jesus Christ

during the conduct of the war. And the

spectacle that we have to-day is that of

Christian teachers moving amongst the war

incidents of the Old Testament in order to find

texts to justify this terrible conflict... This

war is not going to end militarism, the method

is wrong – "Satan cannot cast out Satan";

but Christianity as the antidote to evil has

never yet failed when it has been fairly put to

the test. To-day we are talking about

"national honour," and "national prestige," and

imagining that these are synonymous with

"civilization" and "Christianity;" and Germany

is doing the same. But British honour and

German culture, which need the protection of

dreadnoughts and compulsory military training,

may well be submitted to question.

['Pax', The

Methodist, 17 July 1915]

The editorial bias of The Methodist

can be gauged by a statement appended to this

letter:

We

publish the above, with an apology to our

readers for occupying space with so pitiful if

not puerile a plea for pacifism. It was

sent in by one of our ministers; otherwise we

should not have deemed it worthy of the space

it occupies. – Editor.

Spirited debate continued in the correspondence

pages of The Methodist for another

month. Nine writers were published

attacking Webb's pacifist views; five signed

their names and four chose pseudonyms or

initials. An anonymous writer

– 'Spectator' – called for

pragmatic moral authority to be

applied:

It is

because of the danger to our Christian

civilisation, and because we do not wish the

blood of noble young lives that were dear to us

to have been poured out in vain, that we must

protest against the words of those who, in the

name of the Christian faith, speak in a way

calculated to discourage the efforts of the

nation against an insolent enemy... We

are confronted with circumstances in which we

are to be guided, not by the words of Christ in

a literal acceptation, but by the spirit of

Christian justice and of Christian compassion

for the oppressed. ['Spectator', The

Methodist, 17 July 1915]

'Spectator' also argued for selective reading

of the Bible in a time of war: "The action of

Prussia has thrust our civilisation, for the

time being, some centuries back, and we must

turn for the time to the teaching of the Old

Testament..." Other correspondents

expressed their views more crudely.

'Briton' responded to 'Pax' in the following

terms:

It seems

a pity to give such puerile rubbish as you had

in your issue of 17th inst., so much

prominence. If the writer thinks the

Germans are such angelic beings, let him go to

their country and live.

['Briton', The Methodist, 31 July

1915, p. 11]

A letter from Mr. J. T. Williams contained a

comment directed at 'Pax' which a later

correspondent described as a "veiled threat":

What a

cunning man not to put his name to his

letter! We are just changing

superintendents next Conference, and many other

circuits will be doing the same. Will

some of us be having this pacifist?

['J. T. Williams', The

Methodist, 31 July 1915, p. 11]

Only two writers were published who supported

Linden Webb's pacifist stance; both were

anonymous – the aforementioned 'Pax' and

another named 'Goodwill'. A minister from

South Grafton, Rev. S. C. Roberts, called for a

more temperate debate and was critical of the

biblical ineptitude of some of Webb's

detractors:

Sir,

– Since your "unusual conditions in press

correspondence" makes it necessary to be

personal on this subject, these protests

against Biblical ignorance of "Briton" being

foisted upon us as an oracle and the veiled

threat of Mr. J. T. Williams, shall begin by

stating that I am not an advocate of

peace-at-any-price and my patriotism is as true

and sincere as anyone's... But I do object to

the pillory and abusive terms being applied and

a boycott threatened to those who can't see the

leading that way. The Synod, not the

public press, is the place to discuss a

minister's

character.

['S. C. Roberts', The Methodist, 14

August 1915, p. 9]

The exchange of correspondence was halted by

editorial decree in the issue of 21 August

1915, when it was announced that correspondence

"on the subject of the war" would be

discontinued in the columns of The

Methodist:

So far as

we can see, no good will be done by it; on the

contrary, a great deal of misunderstanding may

arise and no small amount of irritation be

caused. Men are entitled to their own

points of view; and in ordinary times it is

wise to allow considerable liberty in the

expression of opinions, however diverse they

may be. But these are the days of the

censor, on one hand, and of grave national

crisis on the other. Liberty is therefore

necessarily and wisely abridged, for the time

being. Our pacifist brethren must wait

for a more convenient season, and those who

differ from them must give them credit for

sincerity. To continue the discussion in

our columns at the present time would create an

impression of divided counsels in our church at

a time of great stress in national affairs, and

would do us harm. Moreover, in the

interests of those who write in what we regard

as an inopportune and unfortunate strain it is

not desirable to print their letters.

There is no need for them to run the risk of

being gravely misunderstood and of exciting

prejudice that may operate against them for

years. Our business now is to see the war

through.

['The "War" Correspondence', The

Methodist, 21 August 1915, p. 9]

Linder has described Webb's pamphlet, The

Religious Significance of the War, as "the

most tightly argued case for biblical pacifism

produced during World War I". He further

comments that "the rough war of words

concerning Linden Webb's views" published in

The Methodist "no doubt increased

Webb's sense of discomfort and added to the

already high level of stress in his life".

Apart from his sermons in the early months of

1915 there is no evidence that Rev. Webb

attempted in any systematic fashion to dissuade

men of his church from enlisting in the armed

forces

[Linder].

In July 1915

the total membership of the Hay Methodist

church was 50 full members and 20 junior

members (under eighteen years of age).

The first of the Hay Methodist community to

enlist into the Australian Imperial Force was

the 25-year-old ironmonger, William Henry

McMahon; he completed his enlistment at

Liverpool in Sydney on 20 April 1915. He

was the son of James Edward McMahon of Orson

Street, who was Junior Circuit Steward of the

Hay Methodist Church and Mayor of Hay from 1910

to 1913. On 12 June 1915 Frederick

Tapscott, a labourer aged 22 years, completed

his enlistment at Liverpool. On 5 August

1915 Frank Alexander Butterworth and John

Alfred Eason both enlisted at

Cootamundra. Frank Butterworth was a

carpenter aged 20 years, the son of William

Godfrey Butterworth, proprietor of a local

building company, Senior Circuit Steward of the

Hay Methodist Church and Mayor of Hay during

1914; John Eason was a 21-year-old coach

driver, the son of William and Emma

Eason. Soon afterwards the terrible

reality of warfare was felt by the Hay

Methodist community and in particular by the

Junior Circuit Steward, James E. McMahon; his

son, William Henry McMahon, was severely

wounded on 12 August 1915 during the Battle for

Lone Pine at Gallipoli, which resulted a few

days later in the amputation of his right arm.

On Friday

night [27 August 1915] Mr. J. E.

McMahon of Hay, received a wire from the

Defence authorities that his son, Mr. William

H. McMahon, who enlisted some time back, and

left Australia only a few weeks ago for the

Front, had been severely wounded. The

message stated that Private McMahon had been

disembarked at Malta, and that his arm had been

amputated. Further news of the

unfortunate lad's progress was promised as soon

as it came to hand. [Riverine Grazier, 31

August 1915]

When McMahon received the telegram from the

army authorities his wife, Ellen, was lying

gravely ill in their Orson Street home,

suffering from pneumonia. The distress

experienced by James McMahon on learning of his

son's injuries was compounded by the death of

Ellen McMahon during that night. The

newspaper report continued:

Early on

Saturday Mrs. McMahon, the boy's mother, died

from pneumonia, at her home in Orson-street,

after a brief illness. A little over a

week ago she caught a chill while attending to

Mr. McMahon, who was suffering from a severe

cold, and she gradually became worse, and

complications set in. Mrs. McMahon, who

was 54 years of age, was born at Plymouth,

England, and came to Australia in 1885.

She and Mr. McMahon were married at Melbourne

in 1887, and of a family of four two sons

survive. The deceased was buried on

Saturday evening in the Hay Methodist cemetery,

the service being conducted by the Rev. B. L.

Webb. Amongst those in attendance were

the Mayor and Mr. McMahon's brother aldermen

and representatives of the Council's

staff. At last night's Council meeting a

motion of sympathy with Alderman McMahon was

passed. The utmost sympathy is felt

throughout the community for the severely

stricken husband in his hour of

loneliness. His other son, Denis,

volunteered for the front only the other day in

New Zealand. [Riverine Grazier, 31

August 1915]

Up to that point Rev. Webb had continued his

pastorate at Hay "without any overt signs of

disapproval" from his parishioners

[Linder].

However, the wounding of William Henry McMahon

at Lone Pine in August 1915 seemed to signal a

shift in the relationship between the minister

and some of his parishioners.

At home

the events at Gallipoli augmented support for

the war. The publication of the first

list of casualties hardened attitudes and the

evanescent enthusiasms of 1914 were replaced by

a grimmer purpose. [Macintyre p. 152]

At a Quarterly Meeting of the Hay Methodist

church, held on 17 November 1915, James McMahon

submitted his resignation as Junior Circuit

Steward for the stated reason that he disagreed

with his minister's views on the war. The

meeting occurred at a time of "growing casualty

lists, which indicated that the war was

beginning to take a heavy toll of Hay

boys".

As the

community mourned its dead and attempts to

persuade the remaining young men to answer the

call to the colours were stepped up, tempers

became frayed and personal relationships

increasingly more tense.

[Linder]

At the meeting Rev. Webb asked those present if

they shared McMahon's viewpoint:

In a

candid but friendly discussion, recorded in

remarkably full detail in the Quarterly Meeting

Minutes, the various church leaders expressed

their opinions. Of the ten laymen present

– McMahon was not there – W.G.

Butterworth, his Senior Circuit Steward, George

D. Butterworth, F. Styman and A. McDowell

thought Webb's view were, in the words of W.G.

Butterworth, "idealistic and impracticable

under present conditions and they should not

have been expressed from the pulpit".

V.L. Roberts, C.W. Naylor and E. Gentle

believed that the minister had done the right

thing in preaching about the war and

sympathized with his ideals, while G.C. Sides,

J. Simpson Myers and A.E. Hitchcock expressed a

measure of agreement with Webb but were

non-committal concerning the appropriateness of

his anti-war sermons. At the conclusion

of their remarks, Pastor Webb thanked them all

for their frankness and for their expressions

of personal good will. They then

proceeded to transact the business of the

Methodist Circuit of Hay. This meeting of

church officials in a small country town in

November, 1915, was probably a fair picture of

how Australian evangelicals in general and

Australian Methodists in particular were split

over the war. [Linder]

McKernan comments "there was no hint of a

censure for Webb" at this meeting "and no one

suggested that he be replaced: no bad result

for pacifism or for tolerance in a small

country town". He adds: "Such a result

warns us against assuming a widespread

acceptance for the pro-war sentiments of the

official church spokesmen".

[p. 30]

Methodist ministers were appointed to circuits

for short periods; initial appointment in New

South Wales was for one year, with each

successive year renewable to a maximum of three

years. Each appointment was authorised by

the Methodist Conference (the annual assembly

of clergy and laity). The constant

turn-over of ministers between circuits enabled

centralised and disciplinary control over the

ministry and is considered a factor in the

steady growth of Methodism during the

nineteenth century.

The

itinerancy of the clergy ensured the more even

apportionment of ministerial talents among the

circuits than would otherwise have been

possible and bound the ministers into a rich

brotherhood based on broadly-shared

experience. [Wright & Clancy p.

39]

In January 1916, in what can be interpreted as

a gesture of approval of Webb's pastoral role

at Hay, a motion was passed to extend an

invitation for Rev. Webb to remain at Hay for a

third year. The motion was moved by W. G.

Butterworth and seconded by Frederick Styman

and it contained a provision that, due to the

insecure financial circumstances of the Hay

church, Rev. Webb should feel free to seek

another pastorate if he so wished

[Linder]. Frederick Styman's

18-year-old son, Henry, had enlisted in the AIF

on 4 January 1916, the eighth of the Hay

Methodists to join up. The next day

Rupert Godfrey Butterworth, another of W. G.

Butterworth's sons, and the 44-year-old John

Thompson Weymouth enlisted at

Cootamundra.

Unemployment and inflation were major factors

contributing to social tensions in Australia by

mid-year 1916. From August to October

community discord was further aggravated by the

issue of conscription. The new Labor

prime minister, William Hughes, had returned

from a visit to England convinced that a

greater effort and sacrifice was needed to win

the war. Australian soldiers were

suffering extremely heavy casualties during the

Allies' 1916 summer offensive. In late

August, in the face of considerable opposition

from within his own party, Hughes announced

that a referendum would be held to seek a

mandate for the introduction of military

conscription in Australia in order to boost

recruitment numbers. The 'Yes' campaign

was firmly supported by Protestant church

leaders, as well as a number of Catholic

bishops. The prevalent Protestant

viewpoint considered the war a moral crusade

and an instrument by which Australia would be

reformed. The corollary of this

perspective was that all citizens should be

participants in such reform. The campaign

opposing conscription was led by the Catholic

Bishop Daniel Mannix (soon to be Archbishop of

Melbourne). Mannix argued the 'No' case

from a socio-political and class-based

perspective, contending that Australia had

already done enough to help Britain.

This

fundamental disagreement about the nature of

the conscription debate arose from the

different perceptions about the war held by

Catholics and Protestants. Mannix opposed

conscription speaking as a private citizen,

giving his views on a political question.

Protestants supported conscription as

clergymen, from their pulpits, giving their

people moral advice as they would about

questions of sexual morality or gambling.

[McKernan p.

37]

In common with other Protestant churches, the

leadership of the Methodist Church

wholeheartedly endorsed conscription, though

Linder points out that resolutions on the issue

passed by state Conferences "were not binding

on the individual Conscience".

In

Methodist practice, such resolutions were

regarded as moral advice and did not have the

force of ecclesiastical law. The care

with which the various conference leaders

addressed their constituencies concerning the

issues of war and conscription indicates that

this was a matter of great sensitivity and

implies that there was disagreement among

Methodists. [Linder]

Nevertheless the Methodist Church's support for

conscription was a source of regret and

agitation for Linden Webb and forced him to

confront his future within the Church.

From early October 1916 he began to correspond

with Rev. William Pearson, President of the New

South Wales Methodist Conference.

Webb was

anxious to learn the church's position on the

moral issues involved in conscription.

Pearson could see none and, thinking the

subject merely political, advised his younger

colleague to keep away from it. In any

case [Pearson argued] the people

preferred to hear about something other than

the war when in church.

[Wright &

Clancy p. 133]

In the end Webb concluded that his position on

"the moral implications of Christian doctrine"

was incompatible with that of the Methodist

Church and sought to resign. In a letter

to Pearson dated 18 October 1916 Linden Webb

explained his position:

At the

beginning of the last year I endeavoured to

state my own view in three sermons, which were

subsequently published. I tried to show

that, however justifiable a war may seem to be

from the moral standpoint of our present day

civilisation, it can never be justifiable from

the moral standpoint of the Christian

Gospel.

I believe

that in the light of the revelation of Jesus

Christ all war (defensive as well as offensive)

is a moral evil. This does not mean that

we are left impotent in the face of aggression

or powerless to protest against wrong: it means

that we have at our disposal moral and

spiritual forces which are mightier to

overthrow evil than all the bullets and

bayonets ever made.

The fact

that the nation was not sufficiently Christian

to avoid war does not seem to me any excuse for

the Church to adapt her message to any plane of

moral judgment lower than that of the

Cross. The failure of the Church to meet

the challenge of national expediency and

militarism and bear an uncompromising witness

against this (and it seems to me) dreadful

iniquity of Conscription reveals still further

how deep is our difference of view concerning

the moral implications of the

Gospel.

On advice from Pearson, however, Webb accepted

an inactive designation, 'Without Pastoral

Charge', for a year or two

[Wright & Clancy p. 133].

Rev. Webb informed the Hay congregation of the decision he had made and his impending departure from the township. A farewell social gathering was held on Monday night, 23 October 1916, "when a large number of church members assembled to say farewell to the Rev. B. L. Webb and Mrs. Webb".

A very pleasant evening was spent, marred only by thought of the impending parting. Mr. Gentle occupied the chair. A lengthy and excellent programme of musical and elocutionary items were gone through interspersed with parlor games. Presentations to Mrs. Webb were made by Miss Nancy Winser on behalf of the elocution class, and by Mr. Naylor on behalf of the congregation, the gifts being a handsome bag and a silver teapot.

James E. McMahon, who was again Mayor of Hay, "handed a cheque to Mr. Webb as a parting gift from members and adherent[s] of the church, and in doing so mentioned the personal friendship existing between himself and Mr. Webb, despite differences of opinion on certain subjects". The chairman, Mr. Gentle, "expressed his regret at the approaching departure of Mr. and Mrs. Webb, and referred briefly to their many excellent qualities".

Particular mention was made of the kindness and sympathy shown to those in trouble, and of the deep spiritual tone which had characterised the message from the pulpit. Further appreciative remarks were made by other speakers, including Mrs. Nissen, Mr. McDowell, Mr. Naylor, and Mr. Goodsir. Refreshments were served, and the gathering brought to a conclusion by the singing of "God be with you till we meet again." [Riverine Grazier, 3 November 1916, 2(3)]

Rev. Webb's resignation from the Hay Methodist

Circuit was formalised at a Quarterly meeting

held on 25 October 1916. The reason for

his resignation, as noted in the minutes, was

that "his views on the war were not those

accepted by the Methodist Church as a whole,

and therefore he felt he could not consistently

remain a paid agent of the Church".

Linder points out that Webb's resignation could

in no way be attributed to local factors; "not

because of any organized opposition in his

congregation or because his salary was in

arrears – which, as a matter of fact, it

was..."

The 'No' conscription campaign of 1916, led by

Bishop Mannix and Frank Tudor (previously

Minister for Trade and Customs in Hughes'

government), obviously resonated with a

significant proportion of the Australian

population. The conscription referendum

was held on 28 October 1916 and was defeated by

a slender margin.

While

Protestant leaders had treated conscription as

a moral issue and had spoken in unison and in

clear, unequivocal terms about the path of

higher duty, the people had set this guidance

aside, following their own lights, voting in

accordance with their material interests and

their perceptions of political reality.

[McKernan p.

41]

The 1916 national conscription campaign had

enormous repercussions in Australia, including

a major split within the Labor Party and the

consequent realignment of political forces with

Hughes and his supporters forming the

Nationalist Party of Australia. The

public debate revived and exaggerated sectarian

and class divisions within Australian society,

which were further exacerbated by the second

conscription referendum a year later. The

conscription campaigns were waged with

rancorous partisanship and opponents of

conscription were freely accused of treason and

disloyalty.

From November 1916

until early 1917 Rev. Bernard Linden Webb was

based at the Central Methodist Mission at 139

Castlereagh-street in Sydney. Rev. Webb

was recorded as a marriage celebrant at Moss

Vale during 1917 to early 1918 in the New

South Wales Government Gazette.

However, Linder states that during this period

at Moss Vale Linden Webb did not work as a

minister, but tried to support his family by

other means; "he tried his hand at

teaching elocution, farming, peddling apples

door to door and clothing sales".

During this period

Prime Minister 'Billy' Hughes made a second

attempt to introduce conscription. The

referendum was held in December 1917 and, after

a bitter and divisive debate, was again

rejected.

The

Hay Methodist volunteers

The Great War honour

board, now located in the Uniting Church in

Lachlan Street, lists the fifteen names of the

men from the Hay Methodist community who

enlisted and served during the 1914-18

war. Of the fifteen names the service

records of all but two were located in the

online database of the National Archives of

Australia. One of the men on the list

joined up in New Zealand and the other could

not be found on the NAA database. The

details below, therefore, relate to the

thirteen Hay Methodist volunteers for

whom NAA records were located.

|

As previously

stated, the first from the Hay Methodist

congregation to enlist was William Henry

McMahon on 20 April 1915, just a month after

Rev. Webb had delivered the last of his

pacifist sermons. Six others enlisted by

the end of the year; the details of the 1915

volunteers are listed below:

- William Henry McMahon;

occupation, ironmonger; son of James and Ellen

McMahon of Orson Street, Hay; enlistment

completed on 20 April 1915 at Liverpool in

Sydney, aged 25 years and 3 months; placed in

the 1st Battalion AIF (Service No. 2179).

- Frederick Tapscott;

occupation, labourer; son of George and Mary

Ann Tapscott of Umberleigh, county Devon,

England; enlistment completed on 12 June 1915

at Liverpool in Sydney, aged 22 years and 8

months; placed in the 3rd Battalion AIF

(Service No. 2440).

- Frank Alexander

Butterworth; occupation, carpenter; son of

William G. and Jane Butterworth of Pine

Street, Hay; enlistment completed on 5 August

1915 at Cootamundra, aged 20 years and 4

months; placed in the 30th Battalion AIF

(Service No. 1249).

- John Alfred Eason;

occupation, coach driver; son of William and

Emma Eason of Cadell Street, Hay; enlistment

completed on 5 August 1915 at Cootamundra, aged

21 years and 5 months (note: religion

recorded as "C of E"); placed in the 30th

Battalion AIF (Service No. 1254).

- John William Matthews;

occupation, saddler; son of John and Annie

Matthews of Alma Street, Hay; enlistment

completed on 21 September 1915 at Cootamundra,

aged 25 years and 11 months (note:

religion recorded as "C of E"); placed in the

2nd Light Horse Training Regiment (Service

No. 2364).

- Arthur George Adamson;

occupation, ironmonger; son of Mrs. Emma

Adamson of Macauley Street, Hay; enlistment

completed on 27 September 1915 at Cootamundra,

aged 22 years and 10 months; placed in the 18th

Battalion AIF (Service No. 3752).

- James Armstrong;

occupation, labourer; son of Mrs. Annie

Armstrong of Parker Street, Hay; enlistment

completed on 30 October 1915 at Cootamundra,

aged 18 years; placed in the 20th Battalion AIF

(Service No. 4057).

|

|

Six volunteers from

the Hay Methodist community enlisted during

1916. The last to do so was Austral

Jacka, who completed his enlistment at

Cootamundra on 24 May 1916, well before the

1916 conscription campaign was underway.

The details of the 1916 volunteers are

below:

- Henry Styman;

occupation, carpenter; son of Frederick and

Evelyn Styman of Hay; enlistment completed on 4

January 1916 at Cootamundra, aged 18 years;

placed in the 2nd Battalion AIF (Service

No. 5445).

- Rupert Godfrey

Butterworth; occupation, public school teacher;

son of William G. and Jane Butterworth of

Pine Street, Hay; enlistment completed on 5

January 1916 at Cootamundra, aged 24 years and

7 months; placed in the 56th Battalion AIF

(Service No. 2126).

- John Thompson

Weymouth; occupation, painter; husband of

Marion Weymouth, of Simpson Street, Hay;

enlistment completed on 5 January 1916 at

Cootamundra, aged 44 years; placed in the 54th

Battalion AIF (Service No. 5465).

- Ronald Fernley Sandow;

occupation, bootmaker; son of John and Eliza

Sandow of William Street, Hay; enlistment

completed on 27 January 1916 at Liverpool, aged

22 years and 5 months; placed in the 30th

Battalion AIF (Service No. 3642).

- Norman Benjamin Myers;

occupation, butcher; son of the late Benjamin

and Jessie Myers and husband of Ivy Myers of

Water Street, Hay; enlistment completed on 21

March 1916 at Cootamundra, aged 23 years and 2

months; placed in the 4th Battalion AIF

(Service No. 6520).

- Astral Jacka;

occupation, grocer; son of John and Mary Jacka

of 'Lamorna', Hay; enlistment completed on 24

May 1916 at Cootamundra, aged 27 years and 6

months; placed in the 1st Battalion AIF

(Service No. 6757).

The two names on the

Hay Methodist honour board for which Australian

records were not located are "C. Fayle"

and "D. McMahon". The first is

almost certainly Cecil Edward Fayle, son of

Edward and Martha Fayle, who was born at Hay in

1889. Cecil Fayle died on 21 May 1962 at

Hay, aged 73 years. The other was Denis

McMahon, son of James and Ellen McMahon and

brother of William Henry McMahon, who enlisted

in New Zealand in mid-1915.

The proportion of

volunteers from the Hay Methodist congregation

was high – approximately one-fifth of the

total number of parishioners. In

comparison the overall enlistments in New South

Wales amounted to 8.8 percent of the

population. The group from which

volunteers could be drawn (males, aged from 18

to 44 years) was just over 23 percent of the

Hay and district population. If this

proportion applied to the Hay Methodist

church-members it can be assumed that virtually

all the eligible men from this assembly

volunteered for service in the Great War.

This can be compared to the Australian

national average for enlistments of 38 percent

(those who enlisted compared to the

total male population aged from 18 to 44

years). Based on these statistics it is

probably reasonable to conclude that Rev.

Webb's strong pacifist principles exerted

little influence on the young men of Hay

Methodist congregation in regard to their

individual decisions to enlist in the

AIF.

The high enlistment

rate of the Hay Methodists is consistent with

the overall enlistment statistics for Hay and

district. There was a total of 642

enlistments (including nine female nurses) from

a population of about 3,420 (municipality of

Hay and the surrounding Waradgery Shire), a

proportion of 18.8 percent of the Hay and

district population. This was more than

double the average enlistment rate for New

South Wales as a whole. If we apply the

23 percent group (males, aged from 18 to 44

years) to these figures, there were 633 males

who enlisted from a total of about 800 of the

Hay and district population who were within the

eligible group, an enlistment rate from the

eligible group of 79 percent (compared to the

national average of 38 percent).

The enlistment

statistics for Hay and district certainly seem

to indicate a high level of enthusiasm and

allegiance to the Empire. During the

Great War enlistment rates were often cited as

a measure of a district's loyalty and were a

source of community self-esteem.

Country

people boasted that rural Australia provided

many more recruits than their proportion within

the total population demanded, that their

patriotism was more intense and that their

young men were more robust and more adaptable,

that they made better soldiers.

[McKernan p.

182]

Recruiters routinely

appealed to a potential volunteer's sense of

local pride, "as if a strong motive for

enlistment were to uphold the honour of the

district"

[McKernan p. 187]. However, consideration

should also be given to the coercive effect on

local men of the social structure of country

towns and civic events associated with the war,

such as patriotic demonstrations and

recruitment meetings:

... the pressure to enlist bore more heavily on

country people who could not hide behind the

anonymity the large numbers in the cities

provided. In country towns recruiters

appealed to individuals whose private

circumstances, employment and marriage status

would have been known to some, at least, of the

other members of the audience... By treating

volunteers as heroes and by elaborately

farewelling each contingent of them, the people

of the country towns created a climate that

would induce other young men to imitate the

recruits.

[McKernan pp. 182-3]

|

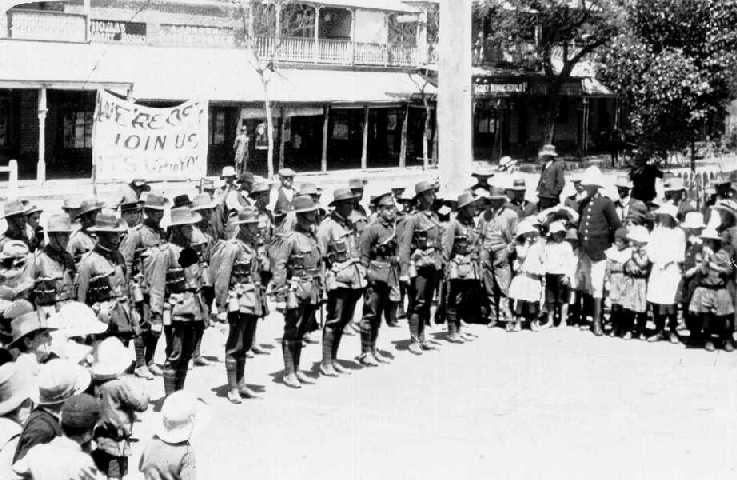

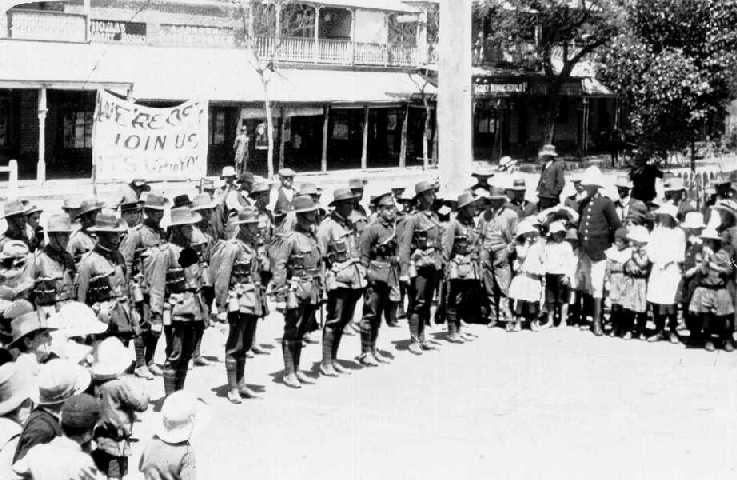

| A ceremony to

farewell troops and recruit new

ones at Hay during World War

I. The banner reads: "We're

off; Join us; It's up to

you." [Fred Harrison

photograph collection (from the

Hay Historical Society’s

CD-ROM, ‘Portrait of

Hay’)] |

The Methodist

volunteers from Hay suffered their share of

casualties and deaths during the

conflict. Four were killed in

action. Arthur George Adamson, of the

18th Battalion AIF, was killed in France on 28

July 1916, aged 23 years. No doubt Rev.

Webb was at hand to provide pastoral support to

Adamson's widowed mother and her other children

when the news of his death reached Hay.

John Alfred Eason was a bombardier in the 14th

Field Artillery Brigade and was wounded in

action on 7 April 1917. He died the next

day at a nearby wound-dressing station.

The other two fatalities were brothers, the

sons of William and Jane Butterworth.

Rupert Godfrey Butterworth, of the 56th

Battalion AIF, was killed in action on 26

September 1917 in France. His younger

brother, Frank Alexander Butterworth, was a

member of the 30th Battalion AIF. Frank

had been wounded in France on 20 July 1916 and

in May 1917 was promoted to Lieutenant. A

month after his brother's death Frank

Butterworth joined the Australian Flying

Corps. He trained in England before going

into action as a scout for the

Australian Divisions, engaging enemy aircraft

and flying observation and contact patrols in

support of the ground troops. Frank

Butterworth was

killed in action on 16 October 1918, less than

a month before the war ended. His

obituary was published in The

Methodist of 23 November 1918:

Lieut.

Frank A. Butterworth, of Hay, had given three

years of his life to the service of the

A.I.F. For the greater part of this time

he was on the battlefield, and proved himself

to be a faithful valiant soldier. He

earned the respect and affection of his

comrades in arms for his courage,

brotherliness, and for his honourable and pure

manhood. "I tried to live like him,"

wrote one of his fellow soldiers. "I made

him my example." He was originally in the

30th Battalion. For bravery in his

battalion he was awarded the Military

Medal. He eventually secured transfer to

the Flying Corps. As a scout, he went

into action, and was killed on 16th October,

little more than three weeks from the

end. The death of this sunny, brave,

capable young soldier cast a gloom over the

town of Hay, where everyone knew and loved

him. Deepest sympathy is felt with Mr.

and Mrs. W. G. Butterworth and their family in

this, the second bereavement they have suffered

during the war, it being almost a year since

their son Rupert made the supreme

sacrifice. Soldiers of Christ, well

done!

A number of the Hay

Methodist volunteers were wounded in

battle:

- William Henry McMahon

was severely wounded on 12 August 1915

during the Battle for Lone Pine at Gallipoli,

resulting in the amputation of his right

arm. He returned to Australia in February

1917. In 1918 he married Winifred Wessler

and the couple lived at Five Dock in

Sydney. William Henry McMahon died in

1970 (registered at Burwood), aged about 80

years.

- Frederick Tapscott was

wounded in action in France on 3 November 1916;

he rejoined his unit in January 1917 and on 20

September of that year received a gunshot wound

to his scalp. In March 1919 he returned

to Australia. Frederick married Catherine

('Kitty') Shephard in 1921 at Hay.

Frederick

Tapscott died at Hay on 8 November 1972,

aged about 80 years.

- Austral Jacka received

a severe gunshot wound to his head on 21

September 1917 in France. He returned to

Australia in February 1918 and was soon

afterwards discharged because of "medical

unfitness". Austral Jacka and Olive

Marteene were married in 1918 in Sydney.

Jacka died in 1950 (registered at Newtown),

aged about 62 years.

Others suffered

injuries and medical conditions while on

overseas duty:

- John Thompson

Weymouth, the oldest of the Hay Methodist

volunteers, fractured his ankle on 8 July 1916

in Egypt and was "invalided to

Australia". He was discharged from the

Army in September 1916.

- Norman Benjamin Myers

was hospitalized on 6 October 1917 with eye

infections (conjunctivitis and trachoma); he

returned to Australia in February 1918 and was

discharged a month later as medically

unfit.

- Ronald Fernley Sandow

was hospitalized on several occasions from

April to September 1918 suffering from a

ventral hernia (the intrusion of an organ

through the abdominal wall in the area of an

old wound or surgical scar). He rejoined

his unit in October and finally returned to

Australia in July 1919.

There is a poignant

postscript to the grief and loss experienced by

the Butterworth family at Hay during the Great

War. Ronald Stanley Butterworth, the

youngest son of William and Jane Butterworth,

enlisted in the AIF in Sydney on 27 September

1918 (a year after his brother Rupert was

killed). Ronald was a law student, a few

months short of his twentieth birthday when he

enlisted; he had previously attempted to join

up but was rejected on medical grounds.

On the form 'Application to Enlist in the

Australian Imperial Force' there is a section

for the consent of parents or guardians in

regard to persons under 21 years. This

section on Ronald Butterworth's form was blank,

though it seems likely his parents were aware

that he had applied to enlist. About

three weeks after he enlisted Ronald's

brother, Frank Butterworth, was killed on the

Western Front. Ronald Butterworth

undertook a course of vaccinations and medical

checks after his enlistment in preparation for

his departure overseas. He was passed fit

for embarkation in November 1918, but soon

afterwards he was discharged from the Army "at

[his] Parents' request". It

seems likely that William and Jane Butterworth

could not bear the possibility of losing a

third son in the war and applied their right to

veto Ronald's enlistment. In any case at

about the same time hostilities between the

warring sides ceased when Germany and her

allies capitulated and signed an Armistice on

11 November 1918.

Linden Webb's

life post-World War I

Rev. B. Linden Webb

was not listed as a marriage celebrant for

1919, but from 1920 to early 1921 he was

appointed as the Methodist minister at

Muswellbrook, NSW.

After the

war, [Webb] applied for reinstatement

as a Methodist minister, and was happily

accepted back into the fold by the New South

Wales Conference. [Linder]

In 1921 Rev. Webb

was at Toronto, NSW, where he remained for

three years. From 1924 to early 1926 he

ministered at Gordon, in suburban

Sydney.

Linden and Eleanor Webb had three daughters and

one son. For part of the period

1927 to 1935 Rev.

Webb served at Norfolk Island. It is

probable, also, that he suffered from bouts of

poor health during this period. In his

obituary Rev. Webb was described as "physically

frail, dogged for many years by ill

health".

Support for pacifist principles grew strongly

within the Methodist church "in the congenial

environment of the 1930s".

The

proposed establishment of the Methodist Peace

Fellowship in 1935, and the designation about

the same time of a 'Peace Sunday', gave the

movement impetus and ensured that the subject

would be kept open to the readers of The

Methodist. E.E.V. Collicott

provided intellectual stimulus, arguing that

the search for peace in the international arena

must be firmly based on its pursuit in our

personal, commercial and national life.

He advised his readers against adherence to

such obsolete concepts as national sovereignty,

since it prevented the proper working of

international machinery. The gentle B.L.

Webb, pleased to find that the atmosphere of

his beloved church had changed over twenty

years, rejoined the discussion, while Revs

William Coleman and Brian Heawood also lent

support as did layman A.O. Robson. Of

course, this was a subject where logical

argument, on either side, did not necessarily

prevail. [Wright & Clancy p.

181]

In early 1937 a United Christian Peace Movement

was formed.

Collicott

was its foundation President and the Anglican,

Rev. W.G. Coughlan of Kingswood, its

Secretary. This provided a broader focus

for those many Christians, both lay and

clerical, in all churches, who were beginning

to find war incompatible with their conscience

and who believed that peace was not the mere

absence of war but 'a positive condition of

society, deliberately and universally based on

the essential Christian principles of truth,

Justice, Mercy, and

Love...' [Wright

& Clancy p. 181]

From 1936 to early 1938 Rev. Bernard Linden

Webb served at Summer Hill, in suburban

Sydney. From 1938 to early 1939 he was

appointed to Campbelltown, NSW. During

1939 Rev. Webb was transferred to Kensington,

in the eastern suburbs of Sydney. With

the outbreak of World War II Rev. Webb felt

"that his pacifist principles were not

consistent with his work in the church" and

resigned from his ministry.

He could

easily have continued his work in the ministry,

and soft pedalled about his views on war, but

he was not that sort of man.

[Collicott]

Rev. Webb spent the remainder of the war-years

supporting his family by selling fruit and

vegetables.

[Collicott]

[Webb]

continued his efforts for peace and

non-violence through such organizations as the

Fellowship of Reconciliation, the Peace Pledge

Union and the War Resisters' International and

joined fellow Methodist ministers Alan Walker

and Harold Rowland in their peace witness

during World War II. [Linder]

Debate about war and peace within the New South

Wales Methodist Church developed a momentum

during and immediately after World War

II. A 'Christian Peace Conference' was

held at the Waverley Church in November 1944,

which was the forerunner of later ecumenical

conferences.

The

advent of the atomic and hydrogen bombs

sharpened the concern for peace because of the

realization that such weapons, for the first

time, gave the human race the power to

annihilate itself. The 1949 New South

Wales Conference declared that 'War today has

become a supreme sin against God and a

degradation of man'. It asserted its

belief in the possibility of peace and called

on all men to support every effort at

reconciliation because 'By the seeking of

social and economic justice for all men, by

generosity of judgements, by casting from

personal and national life the evil which makes

for war, we believe peace can be

secured'.

[Wright & Clancy p. 189]

After World War II Rev. Webb "re-entered the

ministry, but ill-health supervened, and after

a couple of appointments he was compelled to

relinquish normal circuit duties, and retire

into the ranks of the supernumeraries"

(probably at Helensburgh, south of

Sydney).

[McKernan p. 30]

The peace debate received new impetus in the

mid-1960s with the decision to commit

Australian troops to Vietnam. Prominent

Methodists who actively opposed conscription

and Australia's participation in the Vietnam

War included Rev. Alan Walker, superintendent

of the Central Methodist Mission, and Rev. D.

A. Trathan, the headmaster of Newington College

who publicly recommended that young men refuse

to register for National Service. These

ministers and their strong moral stances were

directly connected, by a lineage of peace

activism, to the pioneering pacifist theology

of Linden Webb at Hay during World War I.

Linden Webb's wife, Eleanor, died in

1966. In 1968 Linden Webb's health,

described as "never robust", began to fail,

"and he removed into his daughter's

Convalescent Home [Rima]" at Mosman

[Collicott].

Rev. Bernard Linden Webb died of a stroke on 28

June 1968, aged 83 years, at the Rima Private

Hospital in Mosman.

The

funeral service, which was of a private nature,

was conducted by the Rev. R. Gledhill and the

Rev. F. R. King, at the Mosman Church on

Monday. [The Methodist, 6 July

1968, p. 8]

After Linden Webb's death a tribute by Dr. E.

E. V. Collicott was published in The

Methodist, from which the following is

extracted:

Keenly

alive to the changes of outlook that have come

with the scientific discoveries of recent

years, [Webb] sought and found an

expression for religious faith that satisfied

both the demands of the spirit and the temper

of the age. Thoughtful, tolerant and good

humoured he was a pleasant and stimulating

companion. He saw that life was a

constant becoming, and never became ossified in

his views. With a talent for

verse-writing he embodied much of his vision in

hymns, some of which have appeared in "The

Methodist". For all his gentle modesty he

was inflexibly firm and courageous in

maintaining his convictions. He believed

that war is utterly wrong, and was a

thorough-going pacifist... Three daughters and

a son survive him, and to them we offer our

heartfelt sympathy, together with a sort of

congratulation on the satisfaction they must

feel in the remembrance of a long life loyally

devoted to truth and mercy. [The Methodist, 13 July 1968, p. 14]

References:

'A Place in the World – Culture: Imperial

Ties and World War One', ABC Online,

http://www.abc.net.au/federation/fedstory/ep5/ep5_culture.htm

Census of the Commonwealth of

Australia, 1911.

Census of the Commonwealth of

Australia, 1921.

Collicott, (Dr.) E. E. V., 'Rev. B. Linden

Webb, B.A.: Tribute by Dr. E.E.V. Collicott',

The Methodist, 13 July 1968, p. 14.

Hodge, B., The Last Shilling: Australians

in the Great War, Hicks Smith & Sons,

Sydney, 1974.

Linder, Robert D., 'Galilee Shall at Last

Vanquish Corsica: The Rev. B. Linden Webb

Challenges the War-Makers, 1915-1917',

Church Heritage (Historical Journal of

the Uniting Church in Australia), Vol.

11, No. 3, March 2000, pp. 171-183.

Macintyre, Stuart, The Oxford History of

Australia: Volume 4, 1901-1942, The Succeeding

Age, Oxford University Press, Melbourne,

1986.

McKernan, Michael, The Australian People

and the Great War, Nelson, 1980.

National Archives of Australia, 'A Gift to the

Nation' (online database),

http://www.naa.gov.au/whats-on/online/feature-exhibits/gift.aspx

New South Wales Government Gazette,

lists of registered marriage celebrants.

Scott, Ernest, The Official History of

Australia in the War of 1914-1918, Volume XI:

Australia During the War, Angus and

Robertson Ltd., Sydney, 1936.

Terry, Milton S., Biblical hermeneutics: a

treatise on the interpretation of the Old and

New Testaments, Grand Rapids Michigan:

Zondervan Publishing House, 1974.

Webb, B. Linden, The Religious Significance

of the War, Christian World, Sydney, 1915.

Wright, Don, & Clancy, Eric G., The

Methodists: A History of Methodism in New South

Wales, Allen & Unwin, 1993.

Footnote regarding the Statistics used

in the article:

The assumptions and methods for estimating

enlistment statistics for Hay and district are

as follows: the overall estimated population of

Hay and district during the war was obtained

from the mean of the population data from the

1911 and 1921 Censuses for the municipality of

Hay and surrounding Waradgery Shire (comprising

3,615 square miles); the proportion of males

aged 18 to 44 years was obtained from age

cohort statistics for the county of Waradgery

in the 1911 Census; total enlistment numbers

were obtained from the Hay War Memorial High

School World War I honour board; an assumption

was made that the catchment for names collected

on the HWMHS honour board roughly equates to

the area comprising the municipality of Hay and

the Shire of Waradgery.

National and New South Wales enlistment data

was obtained from

The

Official History of Australia in the War of

1914-1918, Volume XI: Australia During the

War by Ernest

Scott, Angus and Robertson Ltd., Sydney,

1936.

|

Previous newsletters can be accessed by clicking this link

Opinions and comment published in this newsletter reflect the views of the editor. Any corrections, contributions, further information or feedback (critical or otherwise) are welcomed.

© Copyright 2007,

Hay Historical Society Inc.

All rights reserved. The

material in this newsletter is

for personal use only.

Re-publication and

re-dissemination is expressly

prohibited without the prior

written consent of the Hay

Historical Society

Inc.

|

|