|

Welcome to the Hay Historical Society web-site newsletter No. 8. Included in the newsletter is:

'SPECIAL CONSTABLES' AND THE 1894 SHEARERS' STRIKE. – The thematic focus of this newsletter is the 1894 Shearers' Strike. In late August 1894 non-union labourers were transported to Hay in an attempt to provide a strike-breaking workforce in some of the district woolsheds. The adverse reactions of union shearers and subsequent dramatic events at the Hay railway station prompted pre-emptive action by local magistrates, who decided that, "in apprehension of a riot", one hundred 'special constables' should be sworn in to assist the police in "the preservation of the peace and for the protection of the inhabitants". Summonses were issued and a total of ninety-seven 'specials' were sworn in. The men who briefly served as 'special constables' at Hay have been listed on a recently uploaded web-page [link]. Another related web-page reproduces the text of newspaper articles, from the Riverine Grazier and the Sydney Morning Herald, in order to describe the events at Hay in late August 1894 during the 1894 shearers' strike [link]. The feature article in this newsletter expounds further on these events.

HAY SESQUICENTENARY WEB-LOG. – The Hay Historical Society has instigated a project to celebrate the sesquicentenary of the settlement of Hay township, consisting of a web-log of published and other material from 150 years ago relating to the early settlement of the township. Updates will appear on a month-by-month basis, parallel with the events of the time. The material will be supplemented with explanatory passages to contextualise the material. It is envisaged that eventually these accounts will constitute a progressive narrative describing the genesis of Hay township [link]. The monthly web-log instalments will be concurrently published in the 'Blast from the Past' section of the Riverine Grazier.

SHEARS, SHEDS & STRIKES. – A recently published book, Shears, Sheds & Strikes: Australian Sheep Shearing in the Golden days of Wool, 1860-1890, was written by James Donaldson of Hawthorn in Melbourne. The author describes the book as follows:

This is a book about Australian sheep shearing in the Golden Age of Wool in the years 1860-1890. It covers the tradition and craft of the blade shearer and the introduction of the sheep shearing machine from the earliest Australian Patent of 1868 to the successful introduction of the Wolseley shearing machine into the working woolsheds in 1888. It includes materials on sheep stations, woolsheds, wool-washing, shearing conditions, shearing troubles, the rise of Unions in 1886.

I have not had the opportunity to read this book, though I understand it contains a number of references to Hay and Booligal, as well as local stations such as "Kilfera", "Burrabogie", "Toganmain", "Tubbo" (etc.). Shears, Sheds & Strikes is A4 in size with a soft cover, 332 pages in length with over 100 illustrations and an index. The cost is $50.00 (which includes postage); copies can be obtained directly from the author (address: 58 Illawarra Road, Hawthorn, Victoria, 3122).

BUTTERWORTH MEMORIAL HOSTEL FOR GIRLS. – A book detailing the history of the Butterworth Memorial Hostel for Girls at Hay was launched in September 2007. The book is called Butts is Best and was written and compiled by Lyn Brown, Anne Gribble and Wendy Handes (each of them ex-boarders at the hostel). The hostel was established in 1921 as a memorial to two sons of William G. and Jane Butterworth who were killed in World War I. The Butterworth family were stalwarts of the Methodist church at Hay; Rupert Godfrey Butterworth was killed in France in September 1917 and his younger brother, Frank Alexander, was killed in October 1918. The Butterworth Memorial Hostel for Girls was run under the auspices of the Hay Methodist Church and remained in operation until 1956. I have not had an opportunity to read this book; the following is from an account of its launch at Hay:

The hostel provided boarding for hundreds of girls over the years, most of them in the care of Miss Elsie Lonsdale who was matron for almost 30 years. In those days most of Hay War Memorial High School students boarded at one of the several local hostels and the publication covers a variety of subjects associated with Butterworth's hostel. History, personalities and memories are interspersed with photographs, sketches and maps throughout the book. [Riverine Grazier, 3 October 2007]

Butts is Best is in A4 format with 143 pages and includes "many photographs". The cost is $40 (cheques payable to "Butts Hostel Committee"), obtainable from Lyn Brown, at P.O. Box 1437, Griffith, NSW, 2680.

BUTTERWORTH MEMORIAL HOSTEL FOR GIRLS

HAY

(Under the auspices of Hay Methodist Church)

Established in 1921, the Hostel caters for Girls attending Hay War Memorial High School.

All conveniences in congenial surroundings, and full facilities for Study and Sport.

FEES FOR 1947 .. .. .. .. £17 per Term.

For full particulars address all inquiries to

The Matron, Box 23, Hay,

or the Hon. Secretary, Mr. G. D. Butterworth, Box 42, Hay.

[Advertisement, The Methodist, 1 February 1947, p. 6]

|

'SCRAMMY' TYSON UP-DATE. – A Tyson family researcher has provided detailed corrections and additional information about James 'Scrammy' Tyson, whose short biography was included in Newsletter IV (February 2006). The biography has now been amended in the on-line version of the newsletter [link]. The up-dated version is worth reading for the details of 'Scrammy' Tyson's complicated personal life.

The 1894 Shearers' Strike: The 'Hay Riot' and Its Aftermath

The Shearers' Strike of 1894 was the culmination of a decade-long history of negotiation and conflict between labour and capital in Australia. This article describes a series of events at Hay and the surrounding district during a particularly intense phase of the strike. Most commentaries on the 1894 Shearers' Strike focus on violent and confrontational events such as the sinking of the Rodney steamer on the Darling River, the shootings at "Grassmere" woolshed and the exchange of gun-fire at "Dagworth" station in central Queensland. The events in the Hay district demonstrate a more complex and moderate interplay between the protagonists and represent a more measured view of the conflict between the shearers and the pastoralists within the context of the wider rural community.

Background

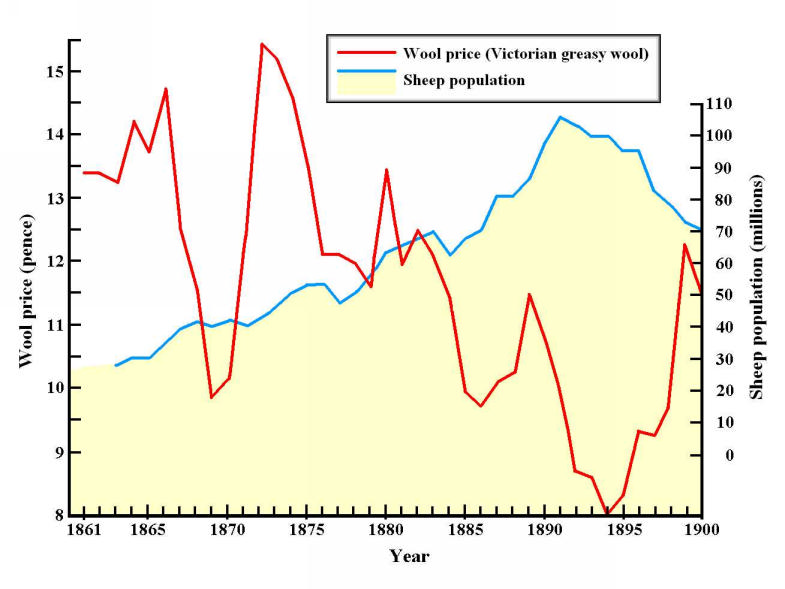

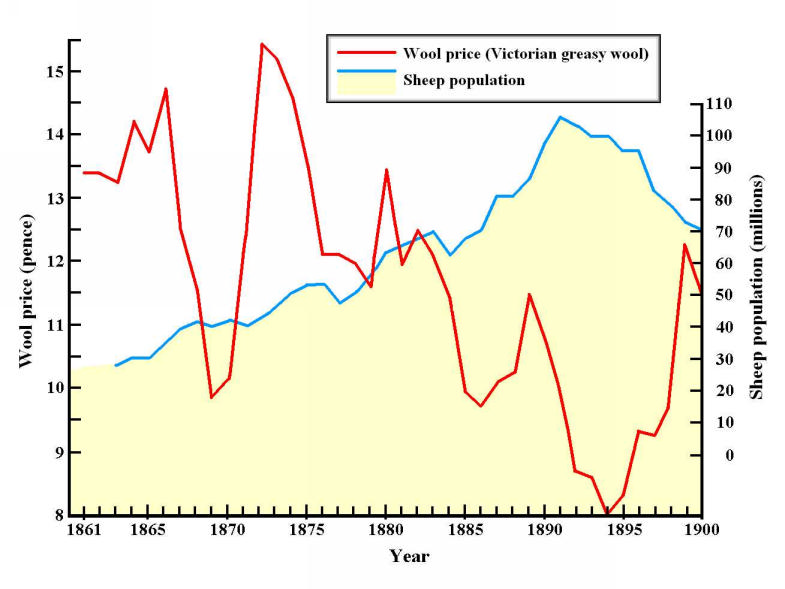

The industrial strife between shearers and their employers in the late 1880s and early 1890s occurred at a time of increasing indebtedness and reduced profitability for pastoralists. During the 1880s pastoralists borrowed in order to finance freehold purchases, improvements (such as fencing and water storages) and pastoral expansion (often into unprofitable marginal land). Productivity declined markedly during the decade due to factors such as the 1883-5 drought, rabbits and soil exhaustion. In 1886 the price of wool suddenly dropped from 12¼d. to 9¼d. a pound. By the end of the decade, with falling wool prices and increasing capital requirements, many pastoral properties were worth less than the amount that had been advanced on them by banks and pastoral companies. Station ownership by financial institutions increased as debts expanded and foreclosures were made.

|

Against a background of declining returns on pastoral investment, regionally-based associations of shearers began to be formed during the late 1880s in an effort to protect shearing rates and conditions. Machine shearing began to be introduced during this period, adding further to the shearers' disquiet. The earliest of the regional unions was the Wagga Wagga Shearers' Union, formed in October 1885. In January 1887 the Amalgamated Shearers' Union of Australasia (A.S.U.) was formed by the combination of unions from Wagga Wagga, Bourke and Ballarat. The annual influx of Victorian shearers to New South Wales, particularly to the Riverina and Darling districts, was a major impetus to the formation of the inter-colonial A.S.U. During the 1887 shearing season disputes occurred which were centred around the issue of the 'second rate', the rate at which a shearer could expect to be paid if he left his employment before 'cut-out' (the completion of shearing). One such confrontation was in August 1887 at "Kilfera" station in the Mossgiel district.

There were eighty stands at Kilfera and within a week some 200 men were in a strike camp near the station. All travellers were met by union pickets, taken to the camp and 'kept'. Finally the deadlock was broken when the parties agreed that dismissed men be paid off at 18s a 100 and that the deducted money go to the ASU. [Merritt p. 111]

Strikes and disputes persisted in the districts surrounding Hay for another month in the wake of the "Kilfera" dispute.

At Toganmain station men who signed the station's agreement were beaten and thrown in the river. Fights between unionists and non-unionists continued in the nearby town of Carrathool and two men were jailed for three months for damaging property. [Merritt p. 112]

Under the leadership of David Temple and William G. Spence the A.S.U. grew in strength over the next few years, gaining in membership and opening new branches. In 1888 the South Australian Shearers' Union merged with the A.S.U.

In two seasons, from being primarily a Riverina and western Victorian union, the ASU had become a truly intercolonial union with a presence in all major pastoral districts in New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia. [Merritt p. 102]

At the annual conference of the A.S.U. at Bourke in 1890 a 'closed shop' rule was adopted, which prohibited members from working with non-union workers. This stance was in direct opposition to the concept of 'freedom of contract', favoured by the pastoralists' unions.

Matters came to a head in Queensland early in 1890 when the Australasian Labour Federation served notice that non-union-shorn wool would be declared 'black' by waterside workers. The test case was non-union-shorn wool from Jondaryan station, which arrived at the wharves to be loaded on the S.S. Jumna. The watersiders refused to load it and the United Pastoralists' Association of Queensland capitulated. [Gollan (1962) p. 604]

In June 1890, as a consequence of these events and in an effort to counter growing union strength, pastoralists formed an inter-colonial body, the Pastoralists' Federal Council. A few days before the inaugural meeting of the Pastoralists' Federal Council in mid-July, the A.S.U., with combative intent, issued a manifesto which declared that the union's objectives would be achieved "by drawing such a cordon of unionism around the Australian continent as will effectually prevent a bale of wool leaving unless shorn by union shearers". These events preceded the Maritime Strike which began in August 1890. The strike initially began on the waterfront, but by September the conflict had escalated as miners, carriers and shearers 'came out' in support. The widespread dispute affected the Hay district; in October 1890 Arthur Rae, the local agent of the A.S.U. at Hay, was charged with inciting shearers to strike. The industrial disruption proved to be futile; non-union labour was in plentiful supply due to high unemployment and police protection for strike-breakers was provided by the colonial governments. By November 1890, with their funds exhausted, the unions were forced to surrender.

Industrial confrontation was rekindled with the beginning of the Queensland shearing season in January 1891. Shearers were 'called out' by the Queensland Shearers' Union as pastoralists enforced the principle of 'freedom of contract' in their sheds. Union camps were established on the outskirts of towns in central Queensland. Non-union labourers were transported to the pastoral districts, often with a military or police escort. Unionists retaliated by attempting to harass the 'blackleg' labourers and committing acts of sabotage, which included the burning of woolsheds, paddocks and fencing. In March police arrested strike-leaders at Barcaldine and Clermont; they were charged with sedition and conspiracy and tried at Rockhampton where thirteen men were each sentenced to three years hard labour.

By mid-year the strike in Queensland was all but over and the A.S.U., after providing financial support to striking Queensland shearers, had little inclination to extend strike action to New South Wales. Nevertheless, scattered strikes in Central Queensland and western New South Wales continued until the eve of a two-day conference between the Pastoralists' Federal Council and the A.S.U., held in August 1891 in Sydney. At this gathering the shearers' union effectively capitulated to the pastoralists by acceding to 'freedom of contract'.

The outcome of that strike was the conference of 1891, at which the Shearers' Union surrendered freedom of contract, and by consenting to the unrestricted employment of men, whether unionists or not, gave up, what, to many pastoralists, was the great objection to the Union. [Riverine Grazier, 31 August 1894]

The accord signed in 1891 by the Pastoralists' Federal Council and the A.S.U. became known as the 'conference agreement'.

In the wake of the 1891 conference agreement the shearing seasons of 1892 and 1893 were relatively quiet. From 1892 to the mid-1890s there was an economic depression in eastern Australia, triggered by a financial crisis in London which resulted in a withdrawal of credit to the colonies.

With pastoral expansion and public investment also nearing their peaks, the [Australian colonies] experienced a speculative boom which added to the imbalances already being caused by falling export prices and rising overseas debt. The boom ended with the wholesale collapse of building companies, mortgage banks and other financial institutions during 1891-92 and the stoppage of much of the banking system during 1893. [Attard]

During 1890 the A.S.U. had began organising shedhands into what became, by early 1891, the General Labourers' Union of Australasia. The Australian Workers' Union (A.W.U.) was formed in February 1894 from the amalgamation of the A.S.U. with the General Labourers' Union.

Whitely King, the Secretary of the New South Wales Pastoralists' Union, wrote to the A.W.U. on 14 April 1894 giving notice that members of the Pastoralists' Federal Council intended to discontinue working under the 1891 conference agreement. In May the Pastoralists' Unions assembled in Federal conference in Sydney, where they proclaimed a new agreement for the impending shearing season which reduced rates for machine shearing. However, for shearers the major cause of concern was Clause 8 of the agreement which placed the sheds under the exclusive control of management, with the owner, station manager or shed boss the sole arbiter in any dispute.

The new agreement [was] so one-sided and so gratuitously insulting that it must needs lead to trouble under any circumstances. It not only reduced wages and broke many of the minor terms of the old agreement, but it contained a proviso that the pastoralist's representative was to be the only court of appeal in all disputes, and his decision was to be final. [The Bulletin, 8 September 1894]

Prelude to the strike

The annual show of the Hay Pastoral Association was held on Thursday and Friday, 26 and 27 July 1894. During show week a private meeting of pastoralists was held in the township, "at which it was decided to adhere to the P.U. (pastoralists' union) agreement in this district".

… we have the best authority for saying that some of the sheds which have always been friendly to the Union have this year decided to shear under P.U. agreement. [Riverine Grazier, 31 July 1894]

Afterwards the co-owner and manager of "Corrong" station, Albert Tyson, had "informed some of the shearers who had engaged pens at that station of his determination to shear under the new agreement". In 1894 the vast pastoral property of "Corrong", 90 kilometres north-west of Hay on the lower Lachlan River, was owned by Arthur and Albert Tyson, the younger sons of the pioneering squatter Peter Tyson. The woolshed on "Corrong" was located on a part of the station known as "Tarwong", about 50 kilometres from the home-station.

In response to these developments a private meeting of shearers was held at the Hay office of the Australian Workers' Union on Saturday morning, 28 July, in order to "consider the whole position, and that with respect to Tarwong especially". The branch office of the A.W.U. had recently opened at Hay under the management of J. R. McDonald, in anticipation of the impending conflict in the district between shearers and pastoralists. That evening a public meeting "of shearers and others" was held at the Temperance Hall in Hay in order to "discuss matters generally". A report of the meeting was published in the Riverine Grazier on 31 July 1894.

There were about one hundred and fifty present, most of them being shearers or shed hands.

The meeting elected E. V. Purcell, a unionist from Wagga Wagga, to take the chair. In his opening remarks the chairman said that "it was not exactly the price they objected to, but that the new proposals would do away with one of the cardinal points of the union, that of the right of the shearers to have a representative in the shed". Purcell was referring to the 8th clause of the Pastoralists' Union agreement which sought to place the sheds under the sole authority of station management. Any shearer who refused to carry out duties as directed (which included the contentious issue of shearing wet sheep) would be in breach of the agreement and be liable for dismissal and forfeiture of earnings or prosecution under the Masters and Servants Act. The union manifesto written in response to the Pastoralists' Union agreement claimed that the 8th clause embodied the principle "that the worker has no rights at all" and was reduced to the level of "a helpless slave" [Merritt p. 235]. A belief that shearing wet sheep caused illness was widespread amongst shearers at that time, so the possibility that they might be legally required to do so was a cause of great concern.

Shearers believed that a wet sheep gave off vapours which found access to their bodies through the pores in their skin and caused aches and swellings in knee joints as well as a number of other internal complaints. [Merritt p. 62]

After Purcell's opening remarks the next speaker at the meeting was J. R. McDonald, the local agent of the A.W.U., who delivered an address of an hour's duration. He began with explanatory remarks about the function and value of the union and countered the speculation (attributed to pastoralists) that "that the union was very nearly broke". McDonald commented on recent confrontations between pastoralists and shearers in other localities and the implications for the impending shearing season in the Hay district:

During the present season in some cases the shearers had resisted the new agreement unsuccessfully, but many more had done so successfully. In Queensland not more than a third of the stations were shearing under Pastoralists' Union agreement. In the Moree and Coonamble districts a large number of sheds were working under conference agreement, but the daily press made no mention of them. [McDonald] gave the names of a number of sheds in the Darling district and in the vicinity of the South Australian border that were shearing under conference agreement…

McDonald explained that in the local and neighbouring districts "no difficulty" had yet arisen, "simply because no shed had begun, except Urangeline" (in the Wagga district east of Urana).

Last year at that station there were about 300 men at the roll-call, and they fell over each other in their eagerness to sign, while this year the shearing had started with 16 men short. These instances showed the difficulty the pastoralists had in procuring labor. Many men, including non-unionists, were staying at home. The position deserved their most earnest attention and would call upon the men for some self-denial, but he had every hope of winning the fight. At Echuca, Swan Hill, and Tocumwal camps were formed, and these had been instrumental in keeping men from Victoria back.

McDonald then addressed more specific local concerns regarding the looming dispute.

There were men in the room who would be asked to sign the Pastoralists' Union agreement at the sheds they were going to, but he hoped they would recognise that it was necessary to make some sacrifice. The fight did not begin until the roll was called, and then was the time when the men should show what they were made of… He did not think there were any shearers about Hay that were not at the meeting, and those would not nearly fill the sheds. He contended that there was not nearly enough men in Riverina to fill the sheds, and if they stuck to their colors he thought they were within easy distance of victory – that was, conference agreement. The Victorians were remaining at home, for which they deserved their best thanks. He urged them to husband their resources and take "a pull" on their expenditure in beer.

McDonald concluded his speech by moving "a vote of thanks to the chairman, and resumed his seat amidst great applause". A shearer at the meeting asked the chairman, E. V. Purcell, about specific tactics to be employed "in the event of men going to a shed and having the Pastoralists' Union agreement put before them".

The Chairman said they should refuse to sign it, and having done that they would have to consider whether they should form a camp or leave the station. He urged them to have no row, but to leave. He asked the men who had no pens not to go on to the station, as the presence of a large number of shearers was bound to encourage the pastoralist to hold out. They would have to exercise a little self denial, and perhaps have a severe struggle, but it was no use "going into the lion's den unless they had a lion's heart." If they formed a camp they should form it at Hay, where they could intercept their fellow-unionists. A camp formed at a station always attracted the police to the scene, and they did not want to give those gentlemen any trouble.

Purcell concluded by urging those present "to stand united in 1894, and they would never regret it"; he expressed the hope that "they would all leave the room good unionists".

The meeting, which was most orderly and very enthusiastic in its appreciation of the speaker's remarks, then dispersed. [Riverine Grazier, 31 July 1894]

The first phase of the strike

During the week following the shearers' meeting reports reached Hay from districts further north "to the effect that the shearing difficulty is causing regrettable delays in the case of many sheds, the men being determined to hold out against the new agreement, and the pastoralists being equally determined to shear under no other". Some of the pastoral properties in the Hay district started shearing operations during that week. From the outset the conditions under which shearers were engaged varied between the stations. At "Tupra" on the lower Lachlan the roll was called on Wednesday, 1 August, and shearers were "engaged without signing any agreement". "Ulonga" station, on the Lachlan River, began shearing on the Thursday, with twenty-six men working under the new Pastoralists' Union agreement. On Friday, 3 August, "Pevensey" started under the 1891 conference agreement. Shearing also began that day at the "Tarwong" woolshed on the "Corrong" run. The intractable stance by the owners of "Corrong" had precipitated the shearers' meeting at Hay six days previously; in the end, however, formal agreements were abandoned at the station:

There was a dispute between the owners [of "Corrong"] and shearers as to which agreement should be used, and eventually it was decided to shear without any agreement at all.

It was reported there were "plenty of men" at the "Tupra" and "Tarwong" sheds in the Oxley district, "and many of them could not find billets".[Riverine Grazier, 3 August 1894] |

|

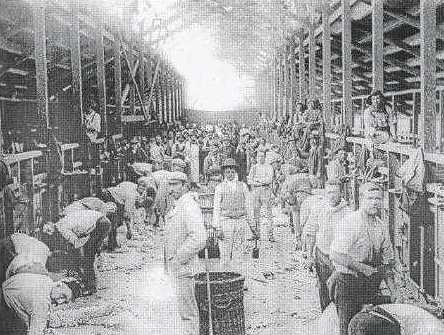

| | "Tarwong" woolshed, photographed in 1898 (from Mackenzie, p. 127) |

|

The resolve by pastoralists to adhere to the 1894 Pastoralists' Union agreement in the Hay and surrounding districts had met with limited success by mid-August, with a number of stations opting to shear under alternative agreements (either the 1891 "conference agreement", their own station agreement or a verbal agreement between the parties). In the Mossgiel district the rolls were called at "Manfred" and "Mulurulu" stations in early August, at which the shearers "declined to sign the Pastoralists' Union agreement". It was reported on 7 August that the striking shearers were in the process of forming a camp about one mile from Mossgiel township, "and they anticipate about 150 men being in camp" [Riverine Grazier, 7 August 1894]. "Gardenia" station started shearing on 10 August "under the conference agreement". The roll was called at "Kilfera" and "Ticehurst" on 13 August where "the men refused to sign the P.U. agreement, and left for Ivanhoe, where a large camp has been formed".

The Marfield men also refused to sign, and a camp of 50 men has been formed near the station. The whole of the shearers are most orderly, and no disturbance is anticipated. The union is supplying the men with rations through the local tradespeople. It is fully expected the men will refuse to sign at all the stations where the P.U. agreement is presented to them. [Riverine Grazier, 14 August 1894]

A meeting of striking shearers was held at Hay on Monday night, 20 August, at the Alma Skating Rink in Lachlan Street. The assembly was addressed by a unionist, John Hart, and the A.W.U. agent at Hay, J. R. McDonald. The purpose of the meeting was to explain to the union-members the current position in the district. A letter from 'A Shearer' was published in the Riverine Grazier of 24 August 1894, which presented a disgruntled account of the meeting. Letters from both J. R. McDonald and John Hart were published in the next issue, refuting statements made by 'A Shearer' and questioning his alliance to the unionist shearers' cause.

"Shearer" must be writing under an alias, otherwise he must belong to the P.U. class of shearers. I can assure you, Mr. Editor, I would consider it an honor to lead the bona fide shearer, but the class of men that "Shearer" evidently belongs to, I would not mix with, much less try to lead. [Correspondence, John Hart, Riverine Grazier, 28 August 1894]

"Mungadal" station, near Hay township, began shearing on Friday, 24 August, "under the Pastoralists' Union agreement with a full board of men". A later report stated that on 3 September "Mungadal" had been "threatened with a raid… but precautions were taken". [Sydney Morning Herald, 30 August 1894; 4 September 1894]

In the Mossgiel district a standoff prevailed at "Mossgiel", "Kilfera", "Conoble", "Boondara" and "Marfield" stations throughout August, where the Pastoralists' Union agreement had been insisted upon. By the end of the month it was reported there were "nearly 500 men in the Mossgiel and Ivanhoe camps, apparently determined to hold out". The conduct of the men at the Mossgiel camp was described as "most orderly", though it was anticipated that "trouble may arise when the free laborers reach the district". [Riverine Grazier, 31 August 1894]

The influx of 'free labourers'

On Tuesday, 28 August 1894, the shearing dispute in the Hay district entered a new phase with the arrival at Hay of fifty-four non-union labourers from Melbourne, accompanied by two agents of the Pastoralists' Union. These men were being transported to the Riverina in order to break the deadlock in the Mossgiel district. Non-union labourers were usually referred to as 'free labourers' in newspaper reports, though unionists were more likely to refer to them as 'blacklegs' or 'scabs'. The men came on a "special train" which travelled from Melbourne via Albury, arriving at the Hay railway-station at half-past eleven at night. [Riverine Grazier, 31 August 1894; Sydney Morning Herald, 29 August 1894]

The train was run right into the engine shed and the doors were closed. There were a number of unionists at the station, and considerable boo-hooing was indulged in. A few stones were thrown through the windows of the building, but with that exception no demonstration of violence was made. A body of police were in attendance, under Mr. Inspector Smith, and guarded the shed during the night. [Riverine Grazier, 31 August 1894]

A supper had been prepared for the 'free labourers' which was "stolen from the engine shed" before the train had arrived; "considerable delay and inconvenience was caused before fresh supplies were obtained".

By the next morning about one hundred unionists and their supporters had gathered within the railway enclosure. At just after eight o'clock four coaches belonging to Cobb and Co. arrived and were halted "outside the northern railway fence". Two of the coaches were drawn by seven horses and the other two drawn by five horses. The unionists within the enclosure "were ordered to go outside the fences, which order was enforced by the police, who drove the men out". The description of what happened next comes from the Riverine Grazier:

One of the seven horse-coaches was then brought into the enclosure near to the engine room, and the gate closed. The coach was driven by Mr. John Keast, and when the team was pulled up the horses faced the west. Some of the police, after backing the unionists beyond the fence, returned to the shed and coach. As the coach was about to pull up, and the doors of the engine room opened to let the free laborers out, the unionists set up a great hooting, advancing towards the coach as they did so. The noise so startled the horses, which had not been brought to a standstill, that they bolted, the driver, although he applied the break, being powerless to pull them up. From where the coach had stood to the cattle trucking yard was about two hundred yards of a straight run, and when the frightened team got to within about forty yards of the stiff fence, the driver either jumped off, or was thrown off, the box. Mr. Keast fell on the near side of the coach in a heap, and the force of his fall was so great that he was rendered unconscious. The fence arrested the progress of the team, but converted it into an indescribable jumble, all but two of the horses, falling. The pole of the coach happened to fit in between two of the rails, and thus the coach escaped without damage. The horses also fared well, for notwithstanding the plight they were in, no bones were broken. Unfortunately, the driver was so seriously hurt that he had to be carried to the hospital on a stretcher. [Riverine Grazier, 31 August 1894]

After the accident the three other coaches returned to Cobb and Co.'s yard and the non-union labourers went back to the engine room. It was later revealed that, during the night prior to the incidents leading to Keast's accident, an attempt had been made to sabotage two of the coaches; "someone entered Cobb and Co.'s yard and removed the near hind axle nut of two of the coaches which were to be used on the following morning".

At the hospital the injured driver, John ('Jack') Keast, was attended to by Doctors Kennedy and Watt. They found that his leg had been badly broken in three places below the knee, "in addition to probable internal injuries". The driver was "put under chloroform" to enable the doctors to set the broken bones. Jack Keast was an experienced local coach-driver, aged in his late 30s. He was married with seven children (the youngest aged about two years). After the accident Keast "remained in an unconscious state for some time". Two days later he was described as being "still in a semi-conscious state, and his position is critical". On 4 September it was reported: "We are glad to be able to say that the condition of the injured driver, Mr. John Keast, is more favorable to-day than it has been since the accident". However, elsewhere in the same issue of the Riverine Grazier it was stated: "We regret to say that Mr. John Keast remains in a critical state, and has made little or no progress towards recovery" [Riverine Grazier, 31 August 1894; 4 September 1894]. Keast eventually did recover from his injuries and continued to drive coaches in the Hay district for at least another ten years. He died in December 1907 in Melbourne.

Later on the day of the coach-accident "a special meeting of magistrates was convened for the purpose of considering the desirability of reading the Riot Act".

The following justices attended:–– Messrs. John Andrew (presiding), A. P. Stewart, A. G. Stevenson, W. H. Barber, W. Travis, N. J. Trevena, and A. Herriott. At this meeting it was unanimously decided that, in apprehension of a riot, one hundred special constables should be sworn in. Steps to carry out that decision were promptly taken.

The police magistrate, Joseph Ede Pearce, "was absent on duty at Booligal, but he returned in the afternoon, and gave in his adherence to what had been done by the honorary magistrates".

Accordingly the nomination of a number of special constables was made. In all, one hundred and thirty-three summonses were issued. Some of these were not served, and some of the persons who were served, although liable to a penalty of £20, did not answer to their names.

The paperwork for the appointment of special constables was worded as follows:

We, Joseph Ede Pearce, and Arthur Herriott, of Hay, Justices of the Peace for the colony of New South Wales, reasonably apprehending that a riot may take place in the town of Hay, and being of the opinion that the ordinary constables or officers appointed for preserving the peace are not sufficient for the preservation of the peace and for the protection of the inhabitants thereof, and the security of the property of the inhabitants thereof, or for the apprehension of any offenders, do hereby in pursuance of Statute 19 Victoria No. 24, nominate and appoint by this writing under our hands the several persons whose names are attached hereto, to act as Special Constables for such time and in such manner as to us shall seem fit and necessary for the public peace and for the protection of the inhabitants, and the security of the property in or near the said town of Hay.

In all ninety-seven 'special constables' were sworn in that evening and the next day (Thursday).

The first batch of specials were sworn in at 8 p.m. on Wednesday, and seven of them were immediately ordered on duty at the railway station. These were relieved at six the following morning by another batch, and from 10 p.m. on Wednesday night to 10 a.m. today, from six to thirteen special constables were constantly on duty at the engine shed. The specials were not armed except for batons, and the only badge of authority they wore was a red band around the left arm. Some of the specials provided themselves with firearms, but others did not even carry the batons that they were provided for them. [Riverine Grazier, 31 August 1894]

On Friday morning, 31 August, a second attempt was made to transport the non-union labourers by coach to stations in the Mossgiel district. Prior to the arrival of the coaches "a representative of the Shearers' Union was allowed to go in to the shed, and ask the men if they wanted to come out, or if they wanted to go in the coaches".

The majority called out "The Coach!" but five expressed their desire to join the unionists, and they were permitted to do so. Earlier in the morning a free labourer had left the shed, and the total defections thus amounted to six.

At nine-thirty a.m. four of Cobb and Co.'s coaches, each drawn by five horses, drew up outside the northern railway fence. By this time all of the 'special constables' were present and on duty.

In addition to the full force of specials there were nearly twenty police on the ground. The foot specials were of little use when it came to keeping the shearers back, but some of the mounted men were more serviceable. The number of unionists on the ground did not exceed one hundred.

The first group of non-union labourers emerged from the engine shed and walked to one of the coaches, "escorted by the police, and without being molested".

The appearance for the free labourers was the signal for hoots, cheers, and cries of "come out !" but the unionists were kept away from the coach by the mounted police until a start was effected. [Riverine Grazier, 31 August 1894]

The report of the incident from a correspondent to the Sydney Morning Herald suggests a more chaotic scene:

The railway station was a scene of the wildest excitement when the men were taken to the coaches. The unionists rushed them, but a strong force of police and special constables managed to keep them back till all the men were aboard. [Sydney Morning Herald, 1 September 1894]

After one of the coaches "had gone about one hundred yards, it was pulled up" and a crowd gathered around it.

The shearers' representative again asked for the men to come out, and Mr. Pearce P.M., who was on horseback enjoined them to adhere loyally to their agreements, and not render themselves liable to punishment. The result was that none of the free labourers left the coach, which then got away without much trouble, and the whole four [coaches] were accompanied out of sight by eight mounted police and a number of mounted specials. [Riverine Grazier, 31 August 1894]

The report in the Riverine Grazier stressed that the unionist shearers "made no demonstrations of violence… beyond hooting and entreating the men to join them", and credited the efforts of "the local representative of the Union, Mr. Macdonald, and one or two of his assistants [who] did their utmost to prevent any breach of the law on the part of the unionists".

The forty-eight non-union labourers who left Hay on Friday morning were intended for "Mossgiel", "Conoble" and "Kilfera" stations in the Mossgiel district. The coaches travelled north along the Booligal Road. The first stop was the Thirteen-mile Gate, the first stage in the journey where the horses were to be changed. This gave the unionists another opportunity to talk to the labourers, and as a result twenty-nine of the men "seceded to the unionists". This left just nineteen of the 'free labourers' to continue towards Booligal on the coaches.

Conveyances have been sent out from Hay by the local Shearers' Union agent to bring the free labourers who left the coaches into the local camp.

The Riverine Grazier reported that some of the 'free labourers' who left the coaches at the Thirteen-Mile Gate later stated "that they would have joined the unionist shearers at Hay, but they were afraid of being arrested for breach of agreement if they did so".

Many of the free laborers were (it is said) hoping that the unionists would rescue them from the engine shed or coaches, so that they would be in a position to say that they had not broken their agreements, but that they had been broken for them. At the 13-Mile stage, the men voluntarily left the coaches… [Riverine Grazier, 4 September 1894]

The remaining nineteen 'free labourers', together with their police escort and a small number of unionist shearers, continued along the Booligal Road. The coaches eventually reached One Tree, where the non-union labourers and the police halted during Friday night.

The unionists who had been accompanying the coaches continued on to Booligal. Earlier that evening a large group of mounted unionist shearers from the Mossgiel, Ivanhoe, and Merrowie Creek camps had arrived at Booligal. The mounted shearers had planned to meet the coaches at One Tree but a "severe thunderstorm [had] detained them at Booligal on Friday". Reckonings of the number of men that gathered at Booligal varied, though "about two hundred" seems to be the estimate closest to the true figure.

All the men were quiet and orderly, and as they passed through the town mounted and leading pack horses they looked a very imposing sight. [Booligal correspondent, Riverine Grazier, 4 September 1894]

The next morning at about 10 o'clock the large group of mounted shearers, together with those who had arrived that night from Hay, left Booligal to meet up with the 'free labourers' and their police escort.

The non-union labourers and the police left One Tree on Saturday morning in two coaches. The leg of their journey from One Tree was uneventful until they reached the Quandongs, where the horses were to be changed. Senior-Constable Gallagher, in command of the police escort, provided the details of the ensuing events which were published in the Riverine Grazier.

Nothing of consequence happened until the horses were being changed at the Quandongs. As the horses were being yoked up, some of the free laborers caught sight of the mounted shearers, who were just coming into view, and Senior-Constable Gallagher's attention was directed to them by hearing one of the passengers exclaim, "Oh ! my God ! see the crowd coming over the hill !" Needless to say, there was no hill, and that the passenger was under the influence of an optical delusion. Mat Hole, one of the drivers, says that at a distance, the mounted shearers looked like a long belt of moving timber.

The senior-constable, mindful of the accident on the previous Wednesday at the Hay railway station, "recommended an immediate start, so that the horses should lose some of their freshness before meeting the cavalcade".

By this time, the police escort had been strengthened by five additional troopers, who had come from Booligal in advance of the unionists, and now consisted of fourteen.

Gallagher commented on the spectacle presented by the mass of mounted shearers:

The men were very well horsed, and there were a good many pack horses among them. The horsemen had been apparently drilled, as they travelled in excellent order, and certainly presented a sight which one might never see again on the plains.

A unionist shearer who had accompanied the coaches from Hay made a similar comment:

The sight of the two hundred mounted men marching towards the coach was one of the greatest military sights even seen in the bush, reminding an old soldier of days seen in service; in fact, it shows what a fine body of men could be put together to defend our homes against a foreign enemy.

When the coaches were within half a mile of the advancing shearers, Senior-Constable Gallagher rode on ahead to met the unionists.

He asked the men, or as many of them as were within reach of his voice, to keep a reasonable distance from the coaches, and not to do anything that would cause an accident. This request did not meet with a cordial acceptance, many of the men speaking at once and expressing their determination to "have them."

Gallagher then asked to speak to "any one who would represent them all". Two delegates came forward, named Forbes and Duggan; they were men "whom Gallagher had known for years". The two shearers asked the senior-constable if they could interview the 'free labourers' "then and there". Gallagher agreed and Forbes and Duggan then rode over to the coaches to converse with the men.

The representatives asked the free laborers to join the unionists, urging that by proceeding to the sheds they were robbing them of their labor. The delegates also said that they had been standing out for the past three months to keep up the price of shearing, and to secure fair terms for the workers. No threats were used. The free laborers listened to all that was said, and then promised to give a decided answer at Booligal.

The coaches then proceeded onwards to Booligal.

The unionist shearers accompanied the coaches for a considerable distance, but went on ahead as they neared Booligal. [Riverine Grazier, 4 September 1894]

At Booligal a crowd of unionists was congregated at the police station, believing that the non-union labourers were to be housed in the lock-up. However, when the coaches reached the township at 4.30 p.m., they proceeded to the hotel.

At the hotel the crowd were very orderly, but some of them showed a disposition to intercept the free laborers as they passed from the coach to the building. Seeing this, Gallagher asked the delegates to let the free laborers get out as ordinary passengers, and interview them in the hotel. Forbes and Duggan having passed the senior-constable's request on to the men, they stood back, and the free laborers got quietly out of the coach.

The shearers' delegates, Forbes and Duggan, "then renewed their requests to the free laborers to join the unionists".

They told them that if they joined, they would take them out to the camp that night, but if they did not wish to go to the camp immediately, they would order tea, supper, and beds for them at the hotel. They also promised to give them pens in preference to men who had been holding out for the last three months. All but two of the free laborers consented to join the unionists, and they elected to have their dinner at the hotel.

The remaining two non-union labourers "held out until the Sunday morning, when they also gave in".

One gave in first, and the other walked down on foot to the camp to get his swag. When he got there, he was asked where he was going to, and he replied that he intended to tramp back to Melbourne. The unionists, however, got him to get up in a buggy, and they drove him off to one of the sheds in the district. [Riverine Grazier, 4 September 1894]

With the capitulation of the last two 'free labourers' on Sunday morning the unionist shearers' victory on this occasion was complete. The Booligal correspondent gave credit to the police in their dealings with the unionists:

Great praise is due to all the police on hand for their tact and forbearance.

Senior-Constable Gallagher made favourable remarks about the behaviour and physical bearing of the union shearers. He described them as "a fine lot, and as orderly a crowd as ever he saw".

Some of them were personally known to him, and many others he knew by sight. The Hay camp will not be flattered by hearing that the senior-constable thinks the men he met at Booligal a superior class to them. They did not offer the slightest violence to any of the free laborers, and did not even indulge in demonstrations of disapproval, such as hooting. Of course, they cheered lustily when they "captured" the coach passengers at Booligal. The men were all apparently in the best of health, and very resolute looking. The two leaders, Forbes and Duggan, are men of splendid physique, and their instructions to the men were loyally obeyed… Although the unionists used nothing but "moral suasion" on the free laborers, Gallagher was not surprised, seeing that the moral suasion was supported by the presence of such a body of determined looking men, that the free laborers gave in. [Riverine Grazier, 4 September 1894]

During the period of the shearing dispute Harold M. Mackenzie, an agent and wool-dealer, was travelling in the Hay district. Mackenzie wrote a series of articles about the stations he visited during this time (which were published in the Riverine Grazier). His contributions included a poem, entitled The Charge of the Two Hundred, about the confrontation on the Booligal Road between the two hundred mounted unionist shearers and the 'free labourers' and their police escort. Mackenzie's satirical poem was written five days after the occurrence, in the style of Tennyson's Charge of the Light Brigade. The tenor of Mackenzie's verse can be judged from the second stanza:

"Who says that we're afraid?"

Shouted brave Jim McQuade.

"Curse the Non-unionists!"

Roared he and thundered

"We're not to turn and fly!

We're but to do and die!"

Over the One-Tree Plain

Rode the Two Hundred. [Mackenzie p. 203]

The Grazier's Booligal correspondent had sent a telegraph to Hay late on Saturday afternoon to announce that all but two of the 'free labourers' "had joined the unionist shearers".

This news was received with general satisfaction at the Union office in Hay, and the feeling of the Mossgiel shearers may be gathered from the following telegram from our Mossgiel correspondent:–– "Great rejoicing here amongst unionists, numbering about 100, result fellow unionists efforts inducing free laborers en route to Mossgiel to desert at Booligal. A contingent of six police are here. Everything is orderly."

That evening "the unionist shearers held a smoke concert and general social" at the Carrington Skating Rink in Leonard Street at Hay.

It differed slightly from the recent smoke concerts at Tattersall's Hotel, inasmuch as no liquor was provided, and in consequence, no toasts were proposed. The local agent, Mr. McDonald, organised an attractive programme of songs and recitations, and, as the men were in good spirits and well satisfied with their week's work, a very enjoyable evening was spent. [Riverine Grazier, 4 September 1894]

The next morning news reached Hay of yet another incident in the district involving non-union labourers. On Friday afternoon, 31 August, twenty-two 'free labourers' had arrived by train at Deniliquin, to be sent to "Dickson's Caroonboon Station and Campbell's Warwillah Station".

There were between 200 and 300 persons on the platform as well as five policeman… the unionists commenced trying by persuasion to induce the men to come out and join their ranks. After some time they induced two, who came out and joined them. [Sydney Morning Herald, 1 September 1894]

Eight of the 'free labourers' left for "Warwillah" station on the Hay mail-coach which left Deniliquin on Saturday night, escorted by two policemen.

At the change, which is about a mile on the other side of Wanganella, twenty mounted unionists met the coach and invited the free laborers to join them, which they refused to do. The coach then proceeded on its way towards Wanganella, where sixty other unionists were waiting for it. Two constables and Mr. Hungerford went in front, and when they met the crowd the constables drew their revolvers and threatened to shoot if they did not disperse. Someone called out, "Fire away!" and nearly all the unionists hooted and boo-hooed. [Riverine Grazier, 4 September 1894]

In addition to the noisy 'boo-hooing' some of the unionists threw sheets of iron in front of Hungerford's buggy, "whereupon the horses turned and bolted, smashed the pole, and threw one of the occupants out". The unionists had erected a barricade across the Wanganella bridge, which "consisted of sheets of galvanised iron placed across the entrance to the bridge, behind which stood the men holding other sheets of iron, forming a close wall of galvanised iron; and in addition to this fencing wire was stretched across the bridge from post to post at the entrance, and the same in the middle of the bridge" [Sydney Morning Herald, 4 September 1894]. When the coach stopped at the barricaded bridge "four of the free shearers were induced to leave the coach".

The leaders of the unionists did not interfere to prevent the other four free men from being forcibly taken away, and it was only through Constable Kilner again drawing his revolver, and threatening to shoot the first who interfered, that I and one or two others were enabled to remove the obstacles, and allow the coach to proceed. [Letter from R. W. Franks of Booabula, Riverine Grazier, 7 September 1894]

The mail-coach arrived at Hay on Sunday morning with news of the interception by union shearers of the coach at Wanganella. Twelve police from Sydney arrived at Hay by train on Monday night, eleven of which continued by coach to Deniliquin. A man named Yohansan was later arrested over the incident; he was charged "with unlawfully assembling with a lot of others and committing riotous acts in the public thoroughfare". Later two more men were arrested and charged "in connection with the late Wanganella outrage". [Sydney Morning Herald, 3, 4 & 6 September 1894; Riverine Grazier, 4 September 1894].

During the week of confrontations over non-union labour there had been indications that compromise positions were increasingly being adopted between the shearers and the managers and owners of a number of the stations in the districts north of Hay. From the Booligal district it was reported that "matters in connection with shearing in this district are very quiet".

The following sheds are shearing under either conference or verbal agreement: Eurugabah, Moolbong, Cowl Cowl, Gunbar and Merungle; the only station in this district shearing P.U. being Alma, with eleven shearers. The roll will be called to-day at Booligal station, verbal agreement. The roll was called this morning at Bank station, and shearing will be commenced tomorrow under the conference agreement. Practically the strike can be considered over, and the men have won the day.

"Manfred" station, in the Mossgiel district, had initially opted for the Pastoralists' Union agreement, but afterwards decided to negotiate a verbal agreement. From the Hillston district it was reported that on many of the stations close to the township "a practical solution of the shearing difficulty has been arrived at". "Hunthawang" station was an exception, with shearing being carried out under the Pastoralists' Union agreement. The smaller homestead lessees in the Hillston district were "all shearing verbal or conference". [Riverine Grazier, 31 August 1894]

The Riverine Grazier devoted its editorial space to 'the shearing difficulty' in the same issue that described the events at the Hay railway station. The editorial began by expressing concern for the detrimental effects to the district caused by the "industrial war that is at present raging".

The great producing interest of the district is being crippled, and thousands of men, able to work, and needing work, are standing out for better terms. The tension between two parties has been growing gradually greater, until it has been found necessary to take extraordinary measures to preserve the peace. The difficulty affects, not only the parties immediately concerned, but also the general community, and it is the duty of all concerned to make use of what influence or weight they possess, to bring about an honorable settlement of the strike.

The Grazier took a reproachful tone in regard to the Pastoralists' Union "standing aloof" from the mutually-agreed 1891 conference agreement in preference to their own agreement which had been "drawn up without any reference to the other party".

The fight is over the Pastoralists' Union agreement, the pastoralists holding out for it and the union shearers holding out against it. Whether that form of agreement be fair or not, it was drawn up without any reference to the other party to it, and it supplants the conference agreement of 1891, which was mutually agreed upon. We believe the pastoralists committed a tactical mistake in not inviting the shearers to a conference over the terms on which they proposed to shear, and, that they should remedy that blunder by doing so now – even although it be late in the day – or promising to do so before the shearing arrangements of 1895 come to be made… Many of the district pastoralists are of the opinion that a conference should have been granted, and others have shown that they do not wholly agree with the action of their executive by conceding the full rate of 20s per hundred. To these we appeal, suggesting that they should recommend the Council of the Pastoralists' Union to agree to a conference, if not for this year for the following ones.

The editorial favoured 'verbal agreements' as a temporary and workable compromise solution:

We see daily by the attitude of the shearers that they are willing to concede almost anything short of the P.U. agreement, and if the pastoralists are equally willing that a solution of the difficulty should be brought about, it seems a sinful waste of time and money that the present strife should be continued. We think the offer of conciliation should come from the pastoralists, for it is they, and not the shearers, who first assumed the aggressive. [Riverine Grazier, 31 August 1894]

'Outrages and acts of violence'

News began to filter through to Hay from the Darling River districts of dramatic events in the dispute between pastoralists and shearers. Two of the most serious incidents, described by the Sydney Morning Herald as "outrages and acts of violence perpetrated by unionist shearers", had occurred a few days before the arrival of the 'free labourers' at the Hay railway station (though it is likely only rudimentary details had reached Hay by that stage) and a week before the events at Booligal and Wanganella. Both of the incidents from the Darling districts, in common with those at Hay, Booligal and Wanganella, involved reactions against non-union labour.

In the early hours of Sunday morning, 26 August 1894, the steamer Rodney was boarded "by a band of disguised men, who took possession of the boat and set her on fire". The Rodney, under Captain Dickson, was transporting about fifty non-union labourers to stations on the Darling River. The steamer had tied up for the night about two miles from "Moorara" station (downstream from Pooncarie). Captain Dickson gave the following account by telegram to Melbourne, to the owners of the Rodney, Permewan, Wright, and Company.

Received warning of the determined attitude of the unionists. The police took every precaution. The manager of Polia and the secretary advised not to proceed past Polia that night pending the arrival of police from Toolan. I tied up the steamer in a swamp and kept a full head of steam on all night. Four men watched on board. On Sunday morning armed men crept cautiously to the boat's head through the water, and on being observed they threatened the man that if he let go the rope they would shoot him. The moment the alarm was given the engine was put full speed astern, but the rope held the boat. The steamer was boarded by a mob at both ends. Some of the mob secured the men, while the rest pillaged the boat, including a cash-box containing £10. The free labourers were dragged ashore, and 10 minutes' notice was given for all hands to leave the boat. The boat was immediately set on fire, kerosene having been poured on the chaff in both holds. The steamer burnt until she sank. It was impossible to scuttle her owing to the great heat of the flames. The boat was completely destroyed. [Sydney Morning Herald, 28 August 1894]

The second incident occurred the night after the burning of the Rodney. A number of 'free labourers' had been transported to "Nettalie" station, in the Wilcannia district, to shear at the "Grassmere" woolshed on the station. Trouble was expected and police were stationed there. On Sunday night (26 August), shortly before nine o'clock, about one hundred unionist shearers arrived in the vicinity of the men's huts at "Grassmere" woolshed.

By mistake they first attacked a hut in which the police (six in number) were camped. [Sydney Morning Herald, 1 September 1894]

The police heard the "stampede of men" and Senior-sergeant M'Donagh emerged to speak to them. The unionists told him that "they wanted to take the free labourers, stating they were armed as well as the police, and were determined to have the men at any cost".

The sergeant replied that they would not be allowed to do so. He was immediately assaulted, and received a blow on the head, felling him to the ground. The mob then rushed the free labourers' hut, smashing the door in with a battering ram. The police fired shots, as also did one of the free labourers, who was armed with a revolver. Two of the unionists were wounded in the affray. Shortly after the shots were fired the unionists retreated, taking the two wounded men with them. The police pursued the mob and arrested six unionists, who are now on their way to Wilcannia, and expected to arrive here to-night. The police took charge of the wounded men, and brought them into Wilcannia in a buggy, arriving here shortly before 1 o'clock to-day [Monday]. Sub-inspector Webb and four constables armed with rifles and revolvers went out to meet the escort, and when about three miles from Wilcannia a mob of unionists, numbering about 500, attempted to stop the buggy with the wounded men. They threw sticks and missiles at the police, and said that if they attempted to move bloodshed would be the result. The police then drew their revolvers on the crowd, which had the effect of subduing them. The escort arrived safely, and the wounded men were taken into gaol. Their names are John Murphy and William M'Lean. [Sydney Morning Herald, 28 August 1894]

Both men had been shot in the chest, with M'Lean's wound considered to be "very critical". Two other unionists received minor wounds during the affray; one had his "left cheek grazed with a bullet", and another "received a shot through the hand". [Sydney Morning Herald, 28 & 29 August 1894]

After the incident at "Grassmere" the unionist shearers were reported to have engaged in several acts of vandalism on the station before they returned to Wilcannia.

The unionists, on returning from Grassmere to Wilcannia, broke down one of the wire-netting gates, on the boundary of Weinteriga and Grassmere, and at another rabbit-proof netting gate, which was only erected about three weeks ago, and placed brush against it, burning it to the ground. The wire and netting were stretched across the tracks for the purpose of wrecking the trap and horses at night, but the attempts proved unsuccessful. [Sydney Morning Herald, 31 August 1894]

Shearing was commenced at "Grassmere" the morning after the incident by the non-union labourers. Six additional police from Broken Hill arrived at the woolshed on 28 August to ensure order was maintained.

The violent events in the Darling country, as well as other incidents such as the actual or attempted burning of woolsheds and fencing in New South Wales and Queensland, resulted in adverse reactions to the unionists' cause from the press, political leaders and the general community. On 31 August 1894, chiefly in response to events in the Darling River districts, a proclamation was published in the New South Wales Government Gazette which declared that "the most stringent measures" will be used against those who, "by combining and acting together", "intimidate and oppressively interfere with certain of her Majesty's subjects in the lawful pursuit of their occupations".

It is hereby notified that all persons offending as hereinbefore mentioned will be rigorously prosecuted as the law directs. And all persons are hereby warned to desist from such unlawful practices; and all subjects of her Majesty are called upon to render assistance in protecting persons from outrage or molestation and in maintaining law and order. [Sydney Morning Herald, 1 September 1894]

'… the whole affair has subsided'

At the Hay Hospital in the early hours of Friday morning, 31 August, a shearer from Victoria named John McCombe died of heart disease. A coffin "with a leaden shell" was constructed so the shearer's remains "could be conveyed to Casterton, Victoria, where the relatives of the deceased reside". On Tuesday morning, 4 September, the union shearers at Hay, in what was described as "an imposing spectacle", carried McCombe's coffin from the hospital to the railway station.

About half past eight this morning, about one hundred and fifty union shearers assembled at the hospital, and forming a procession, marched along Hatty, Orson, and Lachlan streets, in front of the coffin, which was borne on the shoulders of four stalwart men, to the railway station. On arrival at the railway gates, the men formed into two lines, and the coffin, on which some wreaths had been placed, was carried along the lane thus formed, and placed on the train. The men doffed their hats as the coffin was carried past them, and altogether their respectful demeanour formed a marked contrast to that of the previous morning, at the other side of the railway enclosure. [Riverine Grazier, 4 September 1894]

In the wake of the agitation at the Hay railway station, reported in metropolitan newspapers as the 'Hay riot', the Bench of Magistrates had placed an advertisement in the local press to thank the ninety-seven 'special constables' for their services. During the week following the events at the railway station there was an on-going discourse within the township over the issue of the swearing-in of 'special constables' that had occurred on Wednesday and Thursday, 29 and 30 August. The Riverine Grazier considered that "the majority of townspeople think that the step was unnecessary".

There never was any apprehension that the persons or the property of the people of Hay were in jeopardy, and it is doubtful if the unfortunate accident which happened to Driver Keast was a sufficient justification for such a display of force. We believe that if it were necessary to enlist amateur assistance, the swearing-in of a few volunteers would have been ample. As it was most of the specials were unwilling, and but for the penalties attached to refusing to be sworn in, or the possibility of being thought cowardly, they would not have obeyed the summons. A few of the mounted amateurs rendered material assistance…, but those on foot had no apparent influence on the crowd. [Riverine Grazier, 31 August 1894]

The Grazier stressed that many of the 'specials' had been "put to serious inconvenience"; for those "in small businesses, or working for wages, the compulsory service meant loss". A letter from 'Onlooker' was published which echoed this viewpoint, adding that "those who are mainly responsible for the present state of things should be made to pay every shilling which is lost by those who are compelled to act as specials". The correspondent considered those "responsible for the present state of things" to be "those financial institutions which advanced money on station properties in the years past [who] are trying to recover a little of their cash by reducing the number of station hands and their wages".

Of course the manager has simply to do as the directors in Sydney or Melbourne instruct him, no matter what may be his personal opinion on the question… If men are to be sent up, let those who engage them employ also a sufficient escort to land them safely at their destination, instead of having recourse to the law to compel business men and tradesmen to act for the protection of their interests… If the shearers had done anything to place themselves in the power of the law, there would have been plenty of volunteers to prevent anything further happening; but no one can say anything else than that the men were as orderly as it was possible for men to be, and certainly not nearly so noisy as some of our rising generation in the town. [Riverine Grazier, 4 September 1894]

A writer calling himself 'A Special' observed in a letter that, at the railway-station, "the squatters… were conspicuous by their absence" [Riverine Grazier, 7 September 1894]. Another letter, in more satirical style, was written by one who had served as a 'special constable'. The writer, calling himself 'The Same Old Billy', claimed that "we specials don't seem inclined to disband without doing something" and suggested that "the concentrated efforts of 100 desperate specials" be applied to the "goat nuisance" in the township.

While on the subject I would also suggest that, like the Waterloo veterans, we meet at an annual dinner every year to celebrate our great victory of 1894. It will be as well for every man to keep his red rag as a proof that he is a genuine special. In a year or two there will be men laying claim to the honor who have never been sworn in at all. So my advice is: "Stick to your rag." It might be as well to make this raid on the goats before our first annual dinner; it would give us something to talk about. [Riverine Grazier, 4 September 1894]

On Tuesday morning, 4 September, a "deputation of about twenty of the special constables waited on the police magistrate".

Mr. James Newton complained, on behalf of the deputation, that a number of those who were summoned to act as special constables, and who did not obey the summons, were charging those who did so with having acted merely through officiousness, and were saying that they need not have been sworn in unless they wished. Mr. Newton accordingly asked that those who had treated the magistrates' summonses with contempt, should be called upon to explain their conduct or be fined. Other members of the deputation supported the request, including Messrs. Thacker and Terry, who said that they thought it unfair that those who had been compelled to give their time should be misrepresented by others who should have shared their duties. Mr. Pearce agreed with the deputation, and promised that steps should be taken in the direction desired. [Riverine Grazier, 4 September 1894]

The Mayor of Hay, John Andrew, wrote to the Police Magistrate, Joseph E. Pearce, on the same subject:

As a number of citizens summoned to act as special constables last week did not come up for enrolment, and others who were enrolled did not fulfil their duties according to their oath, I respectfully suggest that a call of the Bench be made to decide upon what steps should be made to deal with said delinquents.

The local Clerk of Petty Sessions advised the Riverine Grazier "that the number of those who did not obey the magistrates' summons did not exceed five, and that he will be glad to give the names of these to any one interested" [Riverine Grazier, 4 September 1894]. The Police Magistrate, in his reply on 5 September to the Mayor, recommended no further action in the matter:

Dear Sir, – Your letter of the 4th duly to hand, but before receiving the same, Mr. Newton and several other gentlemen had called upon me making a similar complaint. I immediately called upon the police to give me the names of all the parties they had summoned as special constables who had not responded to their summonses, and I received a report that only three persons had so failed, and of these two had been excused and the other was not served in time to appear. There were many summonses issued for persons who were not served, and this has probably given rise to the current rumor. If, after this explanation, you deem it desirable to call a meeting of the Bench, I will do so, though I would suggest that as the cause and excitement of the whole affair has subsided, it might be as well to let the matter drop. [Riverine Grazier, 7 September 1894]

A report from the Forbes district indicated that the engagement of some non-union labour had been unsuccessful; at the "Burrawang" woolshed "non-union men supplied by the Pastoralists' Union had failed to give satisfaction and were discharged" and shearing resumed there "with a full board of unionists". Several letters to the Riverine Grazier questioned whether the 'free labourers' sent to Hay had been fully informed of the details of the industrial dispute prevailing in the district. The aforementioned letter from 'Onlooker' stated:

I would like to know from any of the Pastoralists' Union agents, or from Mr. Whiteley King himself [secretary of the Pastoralists' Union], if the men they send up to shear are told of the state of things in the country; if so, I do not think they could get any men to sign an agreement to come to these parts. The men who came up this week say they did not know things were in such a state, or they would not have come, and also that they were told they had only a journey of a few miles by coach after getting out of the train, instead of one of one hundred and fifty miles.

William Ewen, writing from Adelaide Camp (near Booligal), expressed himself more succinctly:

Don't blame the free laborers – they were hoodwinked. They were told labor was scarce, not that they were robbing their fellow-men. [Riverine Grazier, 4 September 1894] |

|

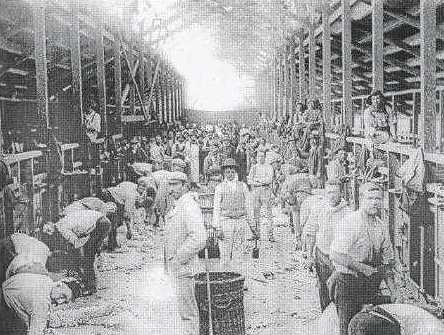

| | [Illustration from The Bulletin, 20 October 1894, p. 14] |

|

In early September it was reported that "Benduck" station had "conceded the conference agreement" [Riverine Grazier, 4 September 1894]. In general, however, it seems that the old-established stations in close proximity to Hay and those with frontages to the Murrumbidgee River had little trouble finding men to work under the Pastoralists' Union agreement. On 5 September a 'representative' of the Riverine Grazier visited the "Eli Elwah" woolshed, "and found shearing busily proceeding under the pastoralists' agreement".

The board was full, twenty-eight shearers being at work, and there was also a full complement of rouseabouts, wool-rollers, etc. Shearing has progressed smoothly since the start, the only delays having been those caused by wet weather. Mr. Melrose, who is in charge of the shed, says that he could not wish for a better lot of men, and that he hopes to cut out in about three weeks' time, if the weather continues fine.

At both "Mungadal" and "Illilawa" it was stated that "shearing is progressing smoothly under the pastoralists' agreement".

At [Illilawa] the board is only about three-fifths full, but Mr. Grant expects to have his full complement of shearers very soon. We are informed that about 1600 sheep a day are being shorn at Mungadal.

In early September it was reported that the "Alma" run, possibly the only station in the Booligal district shearing under the Pastoralists' Union agreement, was "shearing P.U. with three men". Shortly afterwards, however, a number of non-union labourers apparently arrived at "Alma" to bolster the workforce at the woolshed. On Tuesday, 4 September, nearly two hundred unionist shearers arrived at "Alma" station. The account of what happened next, published in the Sydney Morning Herald, describes aggressive behaviour by the unionist shearers.

They rushed the men's huts, and ate the supper prepared for the men. The unionists persuaded the men to come out, but only through fear of the consequences. The men told Mr. Bell, the owner, that they did not want to come out. The unionists then rushed the hut and became most offensive, and by sheer intimidation got the men to leave the station. One policeman gallantly took two free labourers who refused to go with the unionists to the homestead, and kept 40 unionists from taking them by force. Fourteen men were taken away. Several of the unionists were armed, and they tried to take the men who were watching the woolsheds. Not satisfied with what they had done, they robbed the men of several articles of clothing, and stripped the hut of everything they could take. Two police have gone to try and recover the stolen things. [Sydney Morning Herald, 7 September 1894]

This account is at odds with local reporting of the 'shearing difficulty' in the Riverine Grazier, which makes no mention of these dramatic events. What was reported in the Grazier was the response by the station management to what was described as "the rescue of free labourers at Alma". The managing-partner of "Alma" station, Lewis Bell, took out summonses at Booligal "under the Masters and Servants Act for thirteen of the free labourers for leaving their work and for two of the unionists for inducing them to do so" [Riverine Grazier, 11 September 1894]. If the 'free labourers' were taken from "Alma" by force, as the Sydney Morning Herald report states, it is difficult to believe that Bell would respond by taking out summons against thirteen of them "for leaving their work". The veracity of the Sydney Morning Herald report must be questioned and could probably be considered an example of Pastoralists' Union propaganda.

A report reached Hay of "a disturbance of a serious kind" at "Mulurulu" station, about 80 kilometres north-west of Oxley, where shearing was being carried out under the Pastoralists' union agreement. On Friday, 7 September, a group of "about forty unionists" arrived at the station early in the morning.

Two of the men forcibly entered the shearers' hut, and assaulted the manager, knocking him down and inflicting a scalp wound. The manager, in self-defence, fired his revolver, but did not shoot anyone, and the two men then took the revolver away from him. The unionists got five men out without violence or intimidation. There were two police at the station, but they were asleep when the assault took place. When they appeared on the scene, they would have arrested the two offenders, but the manager deemed it prudent not to do so, as he anticipated another attack, and asked the police to remain at the station. Eight shearers are still shearing at Mulurulu. The unionists left about noon. [Riverine Grazier, 11 September 1894]

It was anticipated that the constables at "Mulurulu" would be reinforced with police from Ivanhoe, at which time "the two men who committed the assault will be followed up and arrested".

A week after the deployment of the 'special constables' James Ashton, the Member for Hay in the New South Wales Legislative Assembly, travelled to Hay to personally investigate reports of the 'Hay riot'. Ashton visited the Hay shearers' camp and attended a shearers' meeting on Saturday evening, 8 September 1894. James Ashton had been elected as member for the district in July 1894 and had a close association with Hay township. He had lived at Hay from the late 1870s to the early 1890s (apart from a period of four years in Melbourne). From 1888 to 1892 Ashton owned a half-share in the Riverine Grazier.

The meeting of shearers on the Saturday evening was held at the Academy of Music in Lachlan Street. The assembly was open to the public "and the total attendance was about 200". The local A.W.U. secretary, J. R. McDonald, chaired the meeting, at which several resolutions were discussed and carried. The chairman of the meeting "noticed Mr. Ashton among the audience at the back of the hall, and invited him to address the meeting". In doing so Ashton commented on "the swearing in of special constables in Hay":

When [Ashton] saw the accounts in the newspapers of the swearing in of special constables in Hay, the impression he formed and that formed by most people was that the town was in a state of insurrection. He was glad to have learned since that there was a consensus of opinion that the step was unnecessary, and that the maintenance of order might very well have been left to the ordinary authorities. In this connection, the speaker commended the action of Mr. McDonald, the shearers' agent, during the previous week, in counselling moderation.